Abstract

Psychologists working in a general hospital, such as KAT Hospital, are confronted with patients who have experienced serious accidents and their consequences, such as loss of health, disability, loss of limbs, or even death. Designing appropriate interventions for both patients and their families is essential to help them cope with the new situation in order to reduce the psychological impact of the injury. A case study is presented, involving a woman that suffered amputation as a consequence of an industrial accident, during the pandemic period. During 45 days of hospital stay, multilevel changes were observed in the individual and the family, both physically and psychologically. The main tools used were the genogram and the narrative approach. Communication, the therapeutic relationship, and expressed emotions played a crucial role in the stability and positive outcomes for trauma healing.

Key words: trauma, upper limb amputation, disability, systemic treatment, narrative approach, early intervention in trauma, clinical context.

Presentation of the clinical issue posed by the case

Psychological factors and physical health are linked. The effect of emotions on the body is well documented, both from case observations and from observations in experimental conditions. The quality and nature of the relationships between emotions and bodily functions have shown that emotions are closely related to bodily symptoms. According to psychosomatic medicine, the psyche-body dipole is essentially reducible to the emotion-body dipole. The influence of mental functions on the body is mainly through the autonomic nervous system. An emotional state that is prolonged over a long period of time following a physical injury, mobilizes physiological adaptive mechanisms, and may render them pathogenic and thus trigger pathogenic processes.

This paper discusses early therapeutic intervention in a clinical context, a case study of a patient with a physical injury -upper limb amputation- and the link to psychological trauma from accident day 0 "trauma" to discharge day 45 "healing". Van Der Kolk (2022) states that individuals who have suffered trauma, tend to project their traumatic experience onto everything around them, and often have difficulty deciphering what is happening around them. The imagination and cognitive flexibility of traumatized people is affected, which has consequences on their quality of life. Physical injury affects the body and at the same time, the traumatic experience is imprinted on the body as much as on the mind and brain. This imprint determines how the body manages its survival in the present.

The benefits that traumatized patients gain on a physical and psychological level when the psychologist-psychotherapist helps them find the right words to describe their experience are immeasurable. One of the greatest benefits is the avoidance, in some cases, of the onset of post-traumatic stress disorder. In the analysis of this case, the intergenerational trauma of disability through physical injury/amputation in the present emerged.

Theoretical framework

What is trauma?

The word trauma comes from the ancient Greek verb τιτρώσκω which means to wound. According to medicine, trauma is described as "the sudden or violent dissolution of the continuity of skin tissues and usually bleeding" (Babiniotis, 2008). On a psychological level, when a person experiences a traumatic event, all his/her psychic powers are activated in order to process the specific experience as best he/she can. When the individual's efforts to manage the situation are not sufficient, internal ruptures are created and the trauma is indelibly recorded in memory and in the body.

Trauma is subjective in nature and an experience can lead to it when a person feels unable to defend themselves, helpless and unable to escape from a serious threatening event, which they are unable to process with the help of previous experiences (Ventouratou, 2009). Therefore, one of the events that can cause trauma is an accident.

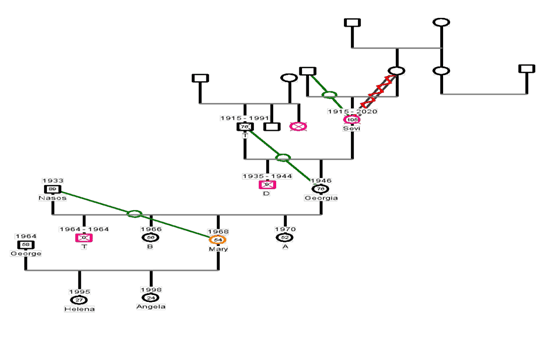

Genogram and intergenerational trauma

The main tool that was utilized was the genogram, and the therapist's approach was inspired by the narrative model. The use of the genogram in clinical practice can help to highlight recurring family patterns and determine preventive interventions in relation to the patient's resources and how they will manage their illness (McGoldrick, Gerson & Petry, 2007). The use of the genogram reveals intergenerational trauma and, as Goodman (2013) states, it becomes the tool for assessment, for strengthening the therapeutic relationship, but also the means to help the therapist make sense of fragmented experiences and memories, to create a narrative memory, and to elaborate on traumatic experiences and emotions with clarity and awareness.

Intergenerational trauma refers to the transmission of trauma from one generation to another (McGoldrick, 2002). The literature emphasizes the role of secrets and the lack of narrative, along with the presence of a sense of crush and shame and the absence of mourning (Bakó & Zana, 2018). More specifically, according to the American Psychological Association (APA)[1], intergenerational trauma is expressed when the descendants of someone who experienced a traumatic event exhibits similar emotional and behavioral reactions to their ancestor or relative. Reactions may include shame, increased anxiety and guilt, increased feelings of vulnerability and powerlessness, low self-esteem, depression, suicide, substance abuse, separation, hyper-vigilance, disturbing thoughts, difficulty in relationships, and attachment to others. The exact mechanisms of the phenomenon remain unknown, but it is thought to have implications onthe way one relates, personal behavior and even attitudes and beliefs that affect future generations.

Atkinson (2017) argues that trauma has gender, race, social and economic class, andis shaped by power relations and privileges. Specifically for intergenerational trauma, she states that it is not disconnected from society and public opinion at any given time. We could think about society's view of the consequences of severe trauma and disability across time. Despite the negative psychological effects of intergenerational trauma, the literature emphasizes that trauma can also lead to the formation of new possibilities and positive ways of coping and making meaning.

Loss and Grief

Kubler-Ross introduced the most commonly taught model for understanding the psychological response to impending death and loss in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying, and described five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance (DABDA model). Loss is accompanied by emotions that are impossible to put into words. The 5 stages of mourning achieve just that. Those five words are the stages that describe the process of grieving and loss. Although the model appears to have a linear progression, in reality there is no linearity as emotions change through time.

The grieving process takes many years and the family has to adapt to the new situation. New roles and tasks are distributed, new close relationships are forged and old alliances change. Most families find a way to come to terms with their losses even though grief does not cease to exist through time, and the pain is eased through determination and fortitude. When families cannot grieve, they become trapped in time, in dreams of the past, feelings of the present, and fears for the future. They are unable to connect with the relationships they maintain in the present and focus on potential losses in the future. Others try to fill the void left by the losses by focusing exclusively on future dreams in order to escape the pain. Often, in cases where no time is given to grieving and there is a rush to move on to the future, the pain returns (McGoldrick, 2002).

Neimeyer (2006) describes mourning as a process of meaning-making. He recognizes that people co-construct how they understand reality through a narrative of their own stories, influenced by their beliefs and worldviews. Grief is both universal and unique, so treatment for the bereaved needs to be tailored to the individual needs of each person. The grieving process is inherently an active rather than passive period, filled with decision-making and reconstruction both on a practical level and an existential one. Consequently,limp amputation is closely linked to the process of mourning and loss.

Disability

In the literature, disability is defined according to the medical and social model. The medical model according to the international classification of disabilities and impairments developed by the World Health Organization in 1980 states: "Impairment is the loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological or anatomical structure or function". Disability occurs at the personal level and is defined by any limitation or loss of the individual's ability to perform an activity in a manner or within the limits considered normal for the human species. The concept of disability is defined as a disadvantage for an individual, as it results from an impairment or disability that limits or prevents the fulfillment of a role that is normal for an individual (depending on age, gender, social and cultural factors). These definitions have been challenged by disability scholars and disabled people (Bakas, 2012).

According to the social model, disabled people do not realize their full potential because of the oppressive impact of a non-disabled society, which operates on the terms of capitalism where a powerful hegemonic class dominates, among others, the powerless disabled (Oliver, 2009). The concepts of harm and disability were studied, appropriately, defined and formed the basis of the social model. Impairment is defined as functional limitation within the individual caused by physical, mental or sensory impairment. While disability is defined as the loss or limitation of opportunities for an individual to participate in the life of a community on an equal level with other individuals due to physical and social barriers. Social issues emerge from disability, and it is no longer seen as an isolated problem, asit is caused by policies, practices and even the environment.

Amputation

The hospital experience and the study of the literature on amputation include both physical disability and psychological distress. It can lead to a decline in a patient's functionality, sensation and body image, and causes strong and varied emotional reactions (Gustafsson & Ahlström 2006; Jo et al, 2021). Doguet et al. (2014) observed that the severity of depression, the functional status of the injured upper limb and the impact of the event improve at a later stage. They also observed that in patients with upper limb injuries, functional outcome at a later stage is influenced by the degree of impact of the event, and the functional status of the hand at the acute stage. Patients may feel as if they have experienced death beyond the concept of physical loss. More specifically, those with traumatic amputations may experience greater difficulties in adjusting. Therefore, patients in such circumstances need immediate intervention from mental health specialists (Bhuvaneswaret al, 2007). Also, patients with traumatic upper limb amputations that were caused by occupational accidents, showed a risk of pathological bereavement. Support and risk control of pathological bereavement are essential in order to limit the psychological impact of trauma and promote social and occupational reintegration (Pomares et al, 2020; 2021).

In a systematic review by Ladds et al. (2016), patients with upper limb amputations or with a tendency to catastrophize, had higher rates of pain. In addition, preventive screening at three months can detect post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression and chronic pain, potentially allowing for early intervention and improved treatment outcomes. To summarize the literature, successful treatment strategies have been proposed in patients with severe upper extremity injuries. Their application is in continuous development and includes not only improved surgical techniques and pharmacological pain management, but also early psychotherapeutic intervention and patient participation in decision-making regarding treatment (Grob, 2008).

The literature review revealed only a few studies of the application of family therapy in cases of amputation (Allan & Ungar, 2012). Amputation is presented as the symptom that affects the homeostasis of the family and leads to the deconstruction and reconstruction of a new one, for the individual, and also for the couple and the family. The exploration and implementation of appropriate interventions are individualized on a case-by-case basis.

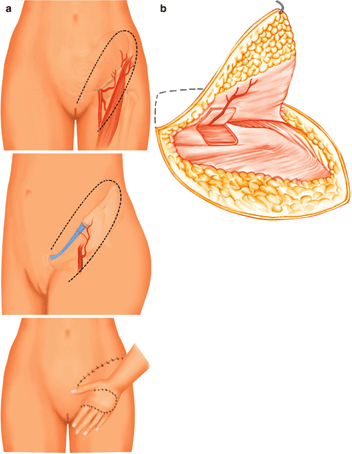

Groin flap reconstruction or Limb Burial

Groin flap reconstruction is a surgical technique used in cases of accidents involving damage to the upper limbs (amputations, degloving, burns, etc.). Often this technique is also called limb burial in medicine. "Ενταφιασμός" in ancient Greek means tomb, "burial", interment; the figurative meaning of the word is the final closure of a case (Babiniotis, 2008). In medicine, the technique of entombment involves placing the injured limb inside the body in order to connect it to vessels so as to initiate perfusion and healing, and thus result in it being "reborn" as it forms new tissues. (Chen et al., 2018, Al-Qattan &Al-Qattan, 2016).

Figure 1. The technique of groin flap reconstruction

Figure 1. The technique of groin flap reconstruction

Self "Reconstruction"

Just as medical science utilizes techniques to reconstruct and heal the injured limb, and gives hope and perspective through the body itself, the science of psychology uses various techniques to reconstruct, rebuild and heal the injured self. As Thanopoulou (2014) aptly states "Humans are narrative beings. We transform our experiences into words, stories, with which we build our relationship with reality as we try to understand and make sense of what happens to us. When we tell our story, we distance ourselves from the events, we relive the experience without being threatened by it, we give it a name as well as a form and a shape. Through the narratives that we tell and retell we seek alternatives, look back to connections with the past and form a perspective for the future; in other words we try to give coherence, order and meaning to our experiences. At the same time, as we share our story we connect with other people with whom, as we interact, we co-construct and reconstruct our stories. The way they listen to us and what is shared in our interaction holds the potential to enrich and evolve our lived reality." Consequently, the narrative approach becomes the "tool" of early intervention after physical injury and contributes to the reconstruction of the self through both spoken and written language (e.g., therapeutic writing). The literature reports the use of therapeutic letters after traumatic events, losses and amputations (Nau, 1997).

Case presentation

The case to be analyzed concerns Maria, 54 years old, who had the fingers of her left upper limb amputated as a result of an industrial accident. Her hospital stay at KAT Hospital lasted 45 days during the Covid-19 period. Day zero "0" is defined here as the day of her injury and surgery. On the same day, the psychologist's office received a request from Maria's family, specifically from her husband, for psychological support and management of the situation. After this accident, Maria was confronted with a new reality. Until then, she had a job and the ability to perform the activities of daily life, which are qualities that she lost after the accident. She suffered a traumatic experience and a surgery, after which she was informed of the loss of her fingers.

1st day: The meeting. The day after the surgery, our first meeting took place in the ward of the clinic where Maria was being treated. It was a room with six beds, where due to COVID-19 restrictions she was alone and remained as such for almost the entire duration of her hospital stay.

Family history

Maria is married to George and they have two daughters 27 and 24 years old. Their daughters are studying in a different city, while the couple lives in a village 150 km away from Athens. The relationships between family members are described as functional and supportive. When talking about herself, Maria mentions that she has been hard working throughout her life, mainly through manual labor. Her outward appearance is well-groomed with a medium stature and thin limbs. On a personality level she is assertive, process oriented, adaptable, supportive, optimistic, giving, and with a positive attitude towards life. There is no reported psychiatric history concerning her or the extended family.

Family background regarding trauma

From the very first meetings, a traumatic story in the family’s history concerning Maria's maternal grandmother is mentioned. In infancy, she had an accident, a fall, as she was not properly held by the hands that cared for her, and as a result she had mobility problems in walking for the rest of her life. This story is described in detail by both her and her husband. This narrative comes during the first few meetings in a natural manner, and it makes me wonder how this information connects to the present.

Figure 2. Genogram

Figure 2. Genogram

Days 1-5: It was during the first few days that the therapeutic relationship was also built. It was not the first time that a clinic had invited me to see a patient after an amputation surgery, but this time the process was new to me due to the mask we had to wear and the distance we had to keep, during the meetings in the hospital ward, due to COVID-19. The therapeutic goal was to manage the altered body image. A body with a loss!

The frequency of the meetings was almost on a daily basis in the hospital room. I tried to connect with Maria with warmth, therapeutic curiosity and neutrality. The priority was to build the connection between us rather than to use a strategy. From the very first contact, Maria's huge smile filled the room as fear and anxiety lurked beneath. I wonder.., how does she manage to smile while being in shock? Just yesterday, she had an accident and a surgery and lost almost the entire palm of her hand. Disconnection is the first thought that crosses my mind. She is having a hard time connecting with her emotions, and she is able to describe the traumatic event in gruesome detail. A freezing of emotions as a form of survival under conditions of intense stress and threat to life.

She mentions the difficulty she has in hearing the word "disability" and in light of this difficulty, the story of her grandmother emerges and she talks about this event and the impact it had on herself. One of these difficulties was her complete aversion to people who had mobility difficulties or disability. She describes how her difficulty in coming to terms with disability was so big, that in the past, at a social event, she had to change seats in order to not be near a fellow guest with disability. She did not want to hear or see disability as she had associated it with negative emotions and negative core beliefs. According to the DABDA model, Maria was in the stage of Denial. Typical of that were her phrases: "I can't believe this happened to me! … I feel like I'm in a dream!"

6th day: On day 6, the physicians decided to proceed to a second operation because of complications that occurred in the healing of the wound. The technique used was groin flap reconstruction or limp burial. In this meeting, I tried to connect through this procedure. I asked her to talk about her experience before and after the surgery, as well as about her emotions. Maria could not accept this new situation and seemed confused and angry,but unable to verbalize these emotions. She was in the stage of anger and some of her phrases were:"Why me? Why now?...."

On the Medical Level

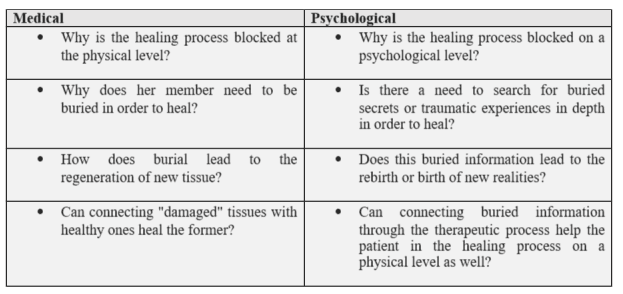

Physicians fused the injured limb with healthy tissue in order to heal it. However, the technique used is particularly interesting, as several connections were observed with Maria's mental state in the present in relation to her intergenerational trauma. Through the supervisory process and the help of the team, some reflections emerged both on a medical level and on a psychological level.

Table 1

Table 1

My presence helped in connecting information with repressed thoughts through narratives, aiming at healing.

Days 13-23: During these days, Maria was open to talking about the traumatic event and making plans for the future. She could imagine herself having a different job. She expressed more easily her difficulty in seeing the physical trauma, her new "body image". She could not identify her emotions and was confused. She was in the process of negotiation and some of her phrases were: "If I had seen the safety button, the engine would have stopped and I wouldn't be here now".

Days 24-34: During these days, as the physical trauma healed, she talked about her past. When asked if there was a need to explore for buried secrets or other traumatic experiences from the past in depth for healing, her response was positive. At this point, the memories were put into words without any therapeutic intervention beyond the therapeutic relationship that had been established. She expressed depression, frustration and crying. She was in the stage of depression.

Day 35: The separation. The third operation was performed. Separation involves releasing the limb from the groin area where it had been placed in order for it to come alive, to be reborn. Maria could describe the image of her hand. She was able to accept it as it was, to embrace it and stroke it. She wanted, however, to be accepted and capable. She seemed to be in the process of acceptance. Some of her phrases were: "I want to protect my little hand." After the surgery the doctors could talk about positive developments in her health.

Days 36-45: During these days, the therapist asked her to write a goodbye letter regarding her loss. Maria committed to writing this letter. A few days before her discharge, she visited me in the psychologist’s office. She had brought the letter, with a smile on her face and a notebook in her hands. That session was highly emotionally charged, as an important cycle was closing for her, and at the same time, we had to discuss our own separation since the therapeutic work was coming to an end. In an atmosphere of mixed emotions, we talked about our short-lived relationship and we agreed that she would come to the Outpatient Clinic of the Hospital after her discharge, at least for as long as she needed to come to the Hospital and visit the doctors who were attending her. She could then seek out a psychotherapist in her area to continue therapy. At that point in time, she felt strong enough to cope with the new reality.

Goodbye letter

"I decided to write a letter, the idea came from a person close to me, who I've only known for a little while, yet she speaks to my soul.

When we write a letter, the recipient is either too far away or we don't want them to interrupt our thinking because we don't care about their opinion. My recipients are gone, lost, rotting away somewhere as if they offered nothing during their lifetime on a body, my body.

I would like, if you could listen to me, to say that I am very sorry for not protecting you; for not appreciating your contribution, over the years; for remembering your appearance; I don't remember if you had any marks, all I remember is that I was bemoaning that you looked old and that I wanted you to be more beautiful. How silly I was… I wish I could go back in time and pet you, cuddle you, spoil you or just look at you. My whole being is mourning. I never imagined that they wouldn't exist in my life… that we would be apart.

I want to thank you for once clinging somewhere, when I was a baby, and helping me walk, for helping me like silent conspirators in my mischiefs, for climbing up the enormous walnut tree, the paddocks, the rocks, everything that contained danger; thank you for giving me food, for through you I caressed, hugged, externalized my feelings, for working tirelessly all these years to help my family financially.

I miss you very much. I hope that when I leave this life you will be somewhere on my path to heaven, and we will be united and NEVER separated.

I LOVE YOU."

Maria

Discussion

Reflections and questions

In this paper, the process of grief and loss is presented through an early intervention in a clinical context while at the same time, Medical and Psychological interventions join hands and travel this path of healing of both physical and psychological trauma. Undoubtedly, psychological factors and physical health are linked. Because the influence of mental functions on the body is mainly through the autonomic nervous system, one of the main goals of the interventions was to avoid pathogenic processes through narrative. At the same time, trauma was processed through intergenerational trauma. I could go on at length about the material that emerges concerning systemic perspectives or letter analysis, but that is not the original aim of this article. I will therefore limit myself to the observation of Psycho-Somatic trauma and healing as presented here,as it seems that in a clinical setting such as KAT Hospital similar interventions could be implemented by specialized therapists.

The therapeutic relationship played a crucial role in the evolution of therapy as it served as a safe place for the expression of emotions and for making sense of new realities. Obviously, questions concerning the DABDA model arose, such as, how structured can the process and procedure of loss be? The question being whether it is sufficient for a clinician to only observe the stages in order for loss to be processed, or whether we need to allow for other skills of the therapist in order for the trauma to be dealt with. Considering individual differences at all levels, we also expect different manifestations of the traumatic experience from patient to patient. However, the question of why some people collapse, become immobilized, freeze, while others move on and manage the loss, remains to be explored by the therapist each time as there is no single answer. What remains the same and what changes in the person's identity after the accident is a question we often ponder on, during supervision. In this case, Maria leaves the hospital with multiple identity changes, one of which is the loss of her job with everything else that this encompasses,both on a family level and on a more personal one.

The role of supervision

The supervision of our clinical work was instrumental in the development of the psychotherapeutic work. As therapists, we address our own anxieties, fears, pains and unresolved issues. The different voices in supervision helped to clarify the landscape for both patient and therapist. Supervision functioned as a safe place that was able to contain all the feelings and thoughts of both the therapist and the patient. In a new condition such as that of COVID-19, the therapeutic work had limitations, such as the use of a facemask. Eye contact and the image of the person as a whole are important tools for therapists, as through facial expression we can also process unspoken emotions. So one of the primary considerations and anxieties was how it would be possible to establish a therapeutic relationship in a clinical setting under these circumstances. Obviously, there is no single answer, and it seems that a therapeutic relationship in this clinical case was established.

Finally, I feel obliged to mention the times when the patient resonated with me through her accounts of both her present and her past. As my experience as a therapist grows in accompanying people in psychologically stressful, critical circumstances, such as hospitalization and loss, my own way of connecting with them changes. Initially, I was under the illusion that I was to be experienced as resilient and invulnerable, probably as a result of my omnipotent approach to my role as a therapist. As I progressed I learned to be more open to my emotions and to allow myself to connect with "vulnerability" through a willingness to accept our human nature.

It is certain that through my own sharing during supervision, I was able to redefine myself each time, to recognize the resonances, and to stay in my therapeutic position giving patients the psychic space that will allow them to transform the pain, to put it into words and narratives in order to be able to renegotiate a sense of continuity and meaning in their lives after the serious injury.

References

Allan, R., & Ungar, M. (2012), Couple and Family Therapy with Five Physical Rehabilitation Populations: A Scoping Review_. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 18(02), 107–134._ doi:10.1017/jrc.2012.13.

Al-Qattan, M. M., & Al-Qattan, A. M. (2016), Defining the Indications of Pedicled Groin and Abdominal Flaps in Hand Reconstructionin the Current Microsurgery Era. The Journal of Hand Surgery, 41(9), 917–927. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.06.006.

Atkinson, M. (2017), The poetics of transgenerational trauma. Bloomsbury Academic, New York_._

Babiniotis, G., (2008), Dictionary of the New Greek language. Centre of Lexicology Ltd., Athens, Greece.

Bakas, E. (2012), Rehabilitation of a Patient with Spinal Cord Injury or Laceration_, from Injury to Reintegration._ Medical Publications Konstantaras, Athens, Greece.

Bakó, T., & Zana, K. (2018), The Vehicle of Transgenerational Trauma: The Transgenerational Atmosphere. American Imago 75(2), 271-285. doi:10.1353/aim.2018.0013.

Bhuvaneswar, C.G., Epstein, L.A., Stern, T.A. (2007), Reactions to amputation: Recognition and treatment. The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 9, pp. 303-308. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v09n0408.

Chen, C., Hao, L. W., & Wang, Z. T. (2018), The use of a free groin flap to reconstruct a dorsal hand skin defect in the replantation of multi-finger amputations. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). doi:10.1177/1753193418805854

Dogu, B., Kuran, B., Sirzai, H., Sag, S., Akkaya, N., & Sahin, F. (2014), The relationship between hand function, depression, and the psychological impact of trauma in patients with traumatic hand injury. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 37(2), 105–109. doi:10.1097/mrr.0000000000000040.

Goodman, R. D. (2013). The transgenerational trauma and resilience genogram, Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(3-4), 386–405.

doi:10.1080/09515070.2013.820172.

Grob, M., Papadopulos, N. A., Zimmermann, A., Biemer, E., & Kovacs, L. (2008), The Psychological Impact of Severe Hand Injury. Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume), 33(3), 358–362. doi:10.1177/1753193407087026.

Gustafsson, M., & Ahlström, G. (2006), Emotional distress and coping in the early stage of recovery following acute traumatic hand injury: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(5), 557–565. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.00.

Jo, S. H., Kang, S. H., Seo, W. S., Koo, B. H., Kim, H. G., Yun, S. H. (2021), Psychiatric understanding and treatment of patients with amputations. _Yeungnam University Journal of Medicine.38(3):194-201._doi:10.12701/yujm.2021.00990.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969), On death and dying, The Macmillan Company, New York.

Ladds, E., Redgrave, N., Hotton, M., & Lamyman, M. (2017). Systematic review: Predicting adverse psychological outcomes after hand trauma_. Journal of Hand Therapy, 30(4), 407–419._ doi:10.1016/j.jht.2016.11.006.

McGoldrick, M. (2002), You can go home again: Reconnecting with your family. Human relations research laboratory, series: Human Systems. Hellenic Letters, Athens.

McGoldrick, Μ., Gerson, R. & Petry S. (2007), Genograms, assessment and intervention. 3rded, Norton, N.Y.

Nau, D. S. (1997), Andy Writes to His Amputated Leg. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 8(1), 1–12. doi:10.1300/j085v08n01_01.

Neimeyer, R. A., Baldwin, S. A., & Gillies, J. (2006), Continuing Bonds and Reconstructing Meaning: Mitigating Complications in Bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. doi:10.1080/07481180600848322.

Oliver, M. (2009), Αναπηρία και πολιτική. Θεσσαλονίκη: Επίκεντρο.

Pomares, G., Coudane, H., Dap, F., & Dautel, G. (2020), Psychological effects of traumatic upper-limb amputations. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2019.12.013.

Pomares, G., Coudane, H., Dap, F., & Dautel, G. (2021), Secondary finger amputation after a work accident. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, 107(5), 102968. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2021.102968.

Pomares, G., Coudane, H., Dap, F., & Dautel, G. (2021), Secondary finger amputation after a work accident. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, 107(5), 102968. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2021.102968.

Thanopoulou, K. (2014), Talking about loss and mourning. Weaving strings of meaning through the grieving process. Systemic Thinking and Psychotherapy, issue 4.

Van Der Kolk, B.,A. (2022), The body keeps the score. Kleidarithmos, Athens.

Ventouratou, D. (2009), Introduction to psychotraumatology and trauma therapy. Pedio, Athens, Greece.

World Health Organization (1980): International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps. Geneva, DC: Author.