Αbstract: In a medical-centered hospital that treats physical injuries after acute accidents, psychotherapeutic works often challenging and frustrating, as it is done under conditions of extreme urgency, intensity, unpredictability and time constriction. The supervision of psychologists has to take into consideration the setting of the hospital with the rigidity and the fragmentation of the dominant medical discourse that reproduces the historical dualism of mind and body. The supervision group explored the application of systems theory to medical practice and built collaborative bridges with physicians and other healthcare providers. We worked based on a metaphor/image: “a body helpless and stuck”. Through the construction of a series of interventions for the patient and his/her family that helped them achieve a sense of agency and better connection, the image evolved to “an injured body that can be inhabited like a house, and participate in an identity building process”. This image had many analogies to the supervisees’ attempt to find their own voice and construct their own identity in the medical setting of the hospital, but also to the supervisor's effort to support and facilitate the therapeutic work of psychologists.

Theoretical background

Until fairly recently, due to the dominance of the biomedical model, little clinical attention was paid to the person's mental health and even less attention was paid to the family. By the end of 20th century, in protest of the over medicalization and dehumanization of care and the disempowerment of patients, the biopsychosocial model of care emerged. Εngel, who developed the biopsychosocial model, believed that to understand and respond adequetly to patients’ suffering- and to give them a sense of being understood – clinicians must attend simultaneously to the biological, psychological and social dimensions of illness (see Borrel- Carrio et al.2004). Engel’s biopsychosocial model took into account the patient as a person and the social context where he or she lives - including the existing healthcare system – in order to comprehend the etiology of illness (Εngel, 1980). Α main concern was the empowerment of patients as persons in order to actively participate in the management of their illness. The next progress of the biopsychosocial model occurred when the specialty of Medical Family Therapy (Med FT) was founded based on the fundamental tenet «that all human problems are biopsychosocial systems problems» (McDaniel, et al,1992 p.26). The practice of Med FT spans a variety of clinical settings with a strong focus on treating patients and their families in relation to health, illness, loss, or trauma using a biopsychosocial-and systemic approach to care. It pays attention to the role that illness plays in the patient’s life, and in the interpersonal dynamics of the family system (McDaniel et al. 1992), as well as the developmental dynamics of the care giving system. Presently, Med FT is based on a biopsychosocial-spiritual systems’ model, after Med FT pioneers recognized the importance of including spirituality in holistic care for the individual and their family.

Μedical Family Therapy that inspired the interventions of psychologists working at the KAT General Hospital of Attica in Greece has two overarching goals: agency and communion (McDaniel et al., 1992). Agency refers to a patient’s personal choices in dealing with illness and healthcare. Sometimes, promoting agency involves helping the patient and their family set limits on the amount of control their illness or disability has over their lives. Other times, promoting agency involves helping the family negotiate for more information or better care arrangements with health professionals. Communion refers to the importance of having familial and community support that can be available to a patient during his/her illness. It refers to the sense of being cared for, loved, and supported by family members, friends, and professionals. The quality of a patient’s social relationships appears to be the most powerful psychosocial factor in someone’s recovery from an illness (McDaniel, Hepworth & Doherty, 1992). In the practice of Med FT both of these concepts help the clinician empower patients to take an active role in their healing process and bring more empathy and compassion into medical practice.

Some thoughts regarding supervision

Supervision is an ongoing, supportive, active learning process that helps clinicians develop, enhance, monitor, and reflect οn their professional role and functioning while attending to ethical and diversity issues in all aspects of the process. Through supervision, supervisees develop their personal and professional selves, become competent and confident in practice, while ensuring patient safety and high quality of care.

The primary task of the supervisor is to help supervisees observe and evaluate the effectiveness of their clinical practice by focusing on:

(1) the relationships they develop with patient and their families

(2) their collaboration with each other and other healthcare professionals, and

(3) the exploration of personal struggles or sensitive issues and concerns of supervisees that interfere with their clinical work and may complicate their clinical effectiveness.

In this direction, it is very important to understand the effects exerted by resonances (Elkaim, 2008), as well as the utilization of the inner voices of the therapist, as aspects of the professional and personal-experienced self that are in conversation and dialogue with each other, according to Rober's model (Rober,1999, 2002, 2005).

Wheller (2007) reminds us that a balance must be struck that enables a degree of exploration and support for the supervisees’ personal concerns, without supervision becoming therapy

Burnham (1993) describes clinical supervision as providing a context where reflexivity can be developed. According to Linnet and Littlejohns (2007), the self-reflexivity that develops in the context of effective supervision can, thus, have the potential to create more effective therapeutic interventions in conjunction with a more highly developed understanding of the recursive relationship between theory and practice. (Linnet and Littlejohns, 2007).

Systemic supervision creates a space that facilitates experiential, transformative learning. It is an interactional, co-evolutionary reflective process, in which supervisor and supervisees are jointly engaged. The creation of new knowledge is not standardized; it is created through the process of conversation and relationship. This knowledge comes from lived experience, is closely connected to emotions and is present in moments of interaction.

Kolb (1984) underlines that learning is defined as “knowledge created through the transformation of experience”, while knowledge “results from the combination of grasping and transforming experience” (p. 41). In this way, learning is stimulated across multiple levels through connections between inner and outer contexts of experience (Neden and Burnham 2007, see also, Charalabaki, Thanopoulou, Kati, 2022).

My approach to supervision places heavy emphasis on the role of meaning, stories, and narratives as relational. People generate meaning jointly with one another through language that includes both the spoken and the unspoken, the verbal and nonverbal (Anderson and Swim, 1995). Meaning emerges through the special nature of the dialectical exchange among the members at a particular moment, and not inside each participant’s mind but rather in the interpersonal space among them (Βakhtin, 1984).

My aim is to promote a relational learning and reflective context with supervisees, in which meaning and knowledge is mutually and collaboratively constructed. Anderson and Swim (1995) point out that learning to be a supervisor is learning how to best participate in the generative process of expanding and creating meaning and action.

The theories and concepts that inform my practice of supervision come from the intergenerational model of Bowen (1996), the attachment theory of Bowlby (1988), the narratives and dialogical psychotherapy (White and Epston, 1990, White, 2007, Anderson, 1997, Bertrando, 2007 etc.), the theory of the dialogical self (Hermans et al.,2004), the polyphonic self of Bakhtin (Baκhtin, 1984), the resonance of Elkaim (2008), and Rober's ideas about the inner voices of the professional self, and the corresponding inner dialogues with the experienced self (Rober, 1999, 2002, 2005). One of my bigger concerns is to facilitate and create a safe, trusting and holding environment for supervisees that values and entails openness, sharing, collaboration, and flexibility. These are conditions that encourage supervisees to discover knowledge and skills, attribute personal meanings to the acquired information, reflect on their experiences with patients, broaden their perspective, and experiment with alternative ways of utilising it in clinical practice.

The supervision system at KAT General Hospital

In 2019, three systemic oriented psychologists that worked at KAT General Hospital of Attica asked me to supervise their work.

Our first connection was systemic thinking -family therapy, and genuine care for people. We shared the belief that the mental and psychic processes are integrally and inextricably linked to the biological ones. At the same time, we were convinced that approaching health from a relational perspective leads to positive health outcomes. Most studies highlight the concept of social support as a factor that can positively influence the outcome of a chronic illness or disability and therefore promotes health. Moreover, there is growing evidence for the mutual influence of family functioning and physical illness or disability (Weihs, Fisher, & Baird, 2002), and the usefulness of family-centered interventions with chronic health conditions (Campbell, 2003).

A deeper, more personal connection was that we all had traumatic experiences with a fragmented healthcare system.

In the beginning I had to be acquainted with the medical culture in general, and the medical setting in particular, which is vastly different than a traditional mental health setting. The work of psychologists in a medical-centred hospital that treats patients with physical injuries after acute accidents - that usually result in handicap or even death - is a challenging, emotionally demanding, and frustrating experience. The medical environment dictates conditions of work under the pressure of extreme urgency, intensity, unpredictability, and time constriction. Another important feature is the hospital setting with the rigidity and fragmentation of the dominant medical culture. The effects of disability on the family and the role family members can play in contributing to health improvement is often ignored by medical doctors that remain organised on a physiological level, and reproduce the historical dualism of mind and body.

We tried to take into account four interlocking systems, the disability, the patient, the family, and the rest of the healthcare team.

As a supervisor, I was faced with the complex task of considering the medical context, the relationships between patients/families, supervisee psychologists, supervisor, and other mental health professionals, as well as the interpersonal and intrapsychic process of all aforementioned parties.

Psychologist’s interventions in three areas:

(a) The Intensive Care Unit is an environment that is extremely distressing for relatives, patients, and healthcare professionals. Patients are exposed to multiple stressors in the ICU, including illness, pain, sleep deprivation, thirst, hunger, dyspnoea, unnatural noise and light, nakedness and lack of dignity, inability to communicate, isolation, fear of dying and witnessing other people suffering and dying. They may also have strong emotional or behavioral reactions in response, including anxiety, panic, low mood, anger, or agitation. Interventions, such as mechanical ventilation (MV) or invasive monitoring for cardiovascular support, may be difficult for patients to tolerate. Furthermore, the onset of delirium, including frightening symptoms such as hallucinations and paranoid delusions, is common in intensive care (Wade, 2016).

Several studies have reported that patients who need intensive care unit (ICU) treatment may experience psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Acute stress in the ICU may be one of the strongest patient risk factors for poor psychological and cognitive outcomes after intensive care (Wade et al. 2012; Davydow et al. 2013).

Families of critically ill patients and ICU staff can also become stressed or traumatized. The period of recovery and rehabilitation after discharge can be prolonged and often impacts on the patient’s and their family’s way of life.

Interventions were planned, as Vagena described in her paper, so as to minimize acute stress for patients and relatives and improve outcomes. The main purpose was to raise awareness and offer information to relatives, aiming at self-care, and management of their patient's course of recovery. Four interdisciplinary, psycho-educational cycles, consisting of five weekly meetings, were held. Individual and family support was provided when necessary. Leaflets were designed and distributed to the relatives who did not attend the meetings.

(b) The Physical Medical Rehabilitation Unit, a place for the treatment of the injured body. Physical disability is a situation that has the potential to affect many parts of a person’s life and that of their family. Physically, mobility restrictions can decrease or completely inhibit a person’s functionality and independence, and quality of life in general, as well as generate incapacity for work. Moreover, psychosomatic disease, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and social isolation are individual consequences interrelated with the physical damage.

Often families must simultaneously manage immediate, intense emotional and practical demands while facing major readjustment issues in their lives, including the uncertainties of a chronic or life-threatening illness and disability, or a prolonged recovery period. They must deal with multiple losses and reorganization of role functioning and relationships, and sometimes face end-of-life issues and bereavement (Rolland and Walsh, 2006)

The psychological adjustment process depends upon an array of personal, functional, and environmental factors, and is idiosyncratic to the individual and their family (Chronister et al., 2021). Each family has its own processes of working through the physical disability. However, the emotional burden for the patient and his/her family is huge. For that reason, psychologists decided to plan sessions with the entire family, when that was possible, in order to alleviate their stress and facilitate their communication skills. We relied on the conceptualization of illness as a relationally traumatizing experience not only for the disabled person but for other members of the family as well, because of its effects on members who also show signs of physical stress, isolation, and helplessness (see Penn, 2001). We strongly believe that encouraging the narration of stories around the experience of disability and suffering, usually supports and strengthens relationship connection, even when this connection seems to include hopelessness, fear, grief, and anger. Stories can act as an antidote to suffering and reflect the family’s attempt to assign order and meaning to a life disrupted by the physical disability. Emphasis is placed on the creation of an atmosphere that helps families and patients feel supported rather than experiencing isolation or anger while coping with the disability (see also Thanopoulou, 2024, in print).

Panou, in her paper, underlined that educating the family regarding disability is one way in which Expressed Emotion can become lowered, so that communication in the family is not hindered. Awareness of the patients’ situation will help them understand and recognize certain behaviors. Assisting families in the acquisition of information and support is essential. While it may help them learn more about their family member’s disability and situation, access to disability-related information and support can also help families reduce stress and improve coping simply by giving an idea of what to expect and anticipate, as well as plan for the future (Rolland, 2006). Another important dimension is to assist families in facing and addressing their own needs and concerns, so they can adapt to the changes brought on by disability, heal emotionally and psychologically, and strive to put their life back together, and move forward in a healthy manner.

(c) trauma management in other clinics. We know from research on trauma that trauma healing narration is characterized by agency, a sense of being the protagonist, the expression of feelings and the construction of personal meaning, a purpose in life, a sense of continuity between past, present and future (see Wigren, 1994).In the clinical case presented by Kasiola, it was evident that the patient’s meaning-making and creation of a new narration helped her make changes in her life, following the physical amputation. Communication and expressed emotions played a crucial role in achieving stability and positive health outcomes. As Frank (1995) comments, illness, in this case disability, threatens not only the body – which mobilizes the need for a new story - but also the identity of the patient. The author points out that illness leads to a loss of the map and the destination that the person has followed up to that point in their life, since they are unable to act independently and feel disconnected from what previously gave meaning to their life. The gap between what they once were, what they are now, what they imagined they would be and what the body now allows them to be, is often very large (see Thanopoulou, 2024, in print). Through her narrative about her disability, Ms. Kasiola's patient tries to repair this rupture, to reconstruct her identity and her life in general, by finding her place in the world again.

Back to the supervision

During our supervision meetings, we had the opportunity to discuss clinical cases and to examine personal, interpersonal and inter-professional dynamics. I, generally, tried to create a space for supervisees to reflect upon, analyze, understand, and process their experiences, in order to develop emotional awareness and use this introspective capacity in the interaction with their patients and families and other health professionals. It was not infrequent, that the dynamics in supervision mirrored the dynamics experienced by families and patients in the face of disability.

A central difficult issue that we were working through was that of emergency, of the ephemeral, and of the emotional burden of clinical work due to the exposure to human suffering and loss. Cecchin and his colleagues (2009), in their book irreverence, remind us “how important it is to somehow manage to survive the doom and gloom that sometimes inevitably occurs when faced with life's tragedies. To manage to continue and not lose hope, to be able to find humor in the absurdity of seemingly impossible situations. Retaining our capacity for excitement and exhilaration, even if we sometimes fail” (Checcin et al., 2009).

Another issue that imposed restrictions and obstacles to psychologists’ clinical work was the medical dominance of the hospital setting with the rigid, technical, impersonal biomedically-oriented style of clinical practice that tended to neglect the human dimension of suffering, devalued the role of psychologists and considered it as as non-essential and substantially ancillary to medical science.

In the beginning of our meetings, I tried to listen carefully to their difficulties and act as a container of their anxieties, fears, angers and frustrations by creating a space in which they could feel safe enough to express their thoughts, feelings and responses. Other times I tried to act as a facilitator of a reflective and explorative process over challenges and adaptations, in an effort to empower them to discover their resources and determine the frame of their interventions.

Until then, medical doctors from the physical medical rehabilitation unit used a strict protocol that imposed to all patients to request psychological help. We tried to facilitate the establishment of a frame of intervention that could be flexible and modified to accommodate the changing needs of patients and families, a frame that could be co-constructed.

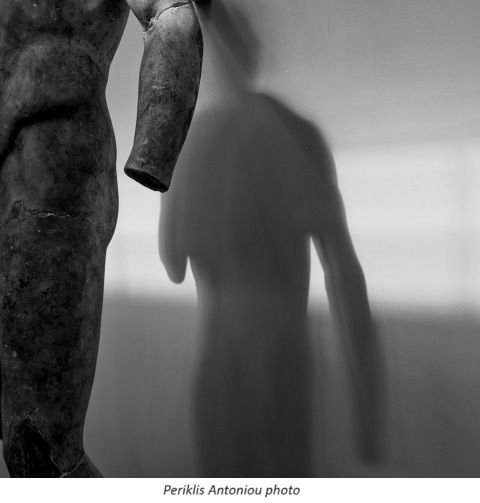

A central metaphor/image that we worked through our supervisory work was that of a «body that is helpless and stuck». We explored how this was isomorphic with the experience of their patients, who also felt weak and helpless following the traumatic injury. My main goal as supervisor had many similarities to the services psychologists offered to physically disabled patients and families. We were very sensitive not to replicate dysfunctional family dynamics. Through the construction of a series of interventions for the patient and his/her family that helped them achieve a sense of agency and better connection, the image evolved to,“an injured body that can be inhabited like a house and participate in an identity building process”. The image of the injured body and the rebuilding process had many analogies to the supervisees’ attempt to find their own voice, construct their own identity and define a clear, recognized role for their profession in the hospital context, as well as with the supervisor’s attempt to support and facilitate their clinical work.

The art of supervision is -as is the art of therapy- the art of conversing in a multiplicity of meanings simultaneously. We believe that supervisors and therapists gain from sharing their work with each other as part of mutual learning and continued professional growth (Anderson, Swim, 1995).

Conclusion

It is my firm belief that supervisees and supervisors gain from sharing their work with each other as part of mutual learning: a learning that focuses on understanding relationships, since it is through them that quality of care is ensured. Through sharing, we explore our experiences, expand our understandings, gain a broader perspective of our role, accept our strengths and limitations and make the inevitable strains of our work more manageable. Chronic and life-threatening conditions force all of us to confront some of life’s greatest challenges. Working with physical disability and loss heightens awareness of our own vulnerability and mortality and reminds us that human suffering is part of our life.

At this point I would like to briefly mention an incident that occurred in the emergency room of KAT Hospital and was discussed during one of our supervisory meetings. A two-month-old baby was accompanied by his parents to the emergency room with a weak pulse. Several hours later, after performing a failed resuscitation attempt, the doctors pronounced the baby dead, probably from aspiration of gastric contents. Inside the medical ward there was bewilderment, numbness, awkwardness, silent sadness.

The image of a dying baby, so incompatible with the life its birth symbolizes, inevitably brings us into contact with unspeakable, unbearable pain and devastation. These are experiences that go beyond the capacity of words to describe them and of the psyche to contain them, experiences that remind us how hard the daily life in a hospital. The doctor, the caregiver, the nurse, the therapist, are also wounded, vulnerable and defense less to the pain of the death of an infant that was found by death before it could actually live.

Undeniably, infant loss is one of the most painful experiences for health professionals. According to Nuzum et al. (2014), the grief of family members that develops in the presence of medical staff, as well as the burden of responsibility at the professional and medical level, take a psychological toll on health professionals. Feelings of pain, shame, guilt and also embarrassment about how the news of the death will be communicated to the parents are often reported.

This whole tragic incident, with the defenseless dead infant, highlighted a crack in the hospital system; a crack that allowed the mental anguish, vulnerability and humanity of the persons who often hide behind the armor of their professional role to become apparent. The premature departure from life of this almost newborn baby brought medical staff members into contact with the fragility of existence and the ephemeral nature of life. All together, as a community, through their gestures, their words, their looks and even their silence, they accompanied the baby to death and, if only for that single moment, they seemed to connect with the most sensitive and vulnerable part of themselves that they are often asked to hide behind the identity of their role.

Brown (2015) defines vulnerability as uncertainty, risk and emotional exposure. It is that weak feeling we have when we step out of our safety zone, or do something that causes us to let go of control. And as he argues, vulnerability is not a weakness but our greatest strength, the point at which all that defines our humanity is born.

The greatest healer of pain in Greek mythology was an injured healer named Chiron. The etymology of his name implies that he healed through the touch of his hand. Chiron, who was a charismatic centaur (half man-half horse), was accidentally hurt in the knee by a student of his, Hercules, and this accident forced him to slow down and pay attention to the equine part of his body, the part that had caused his mother to abandon him at birth and consequently mentally traumatised him. Because Chiron was immortal, he struggled with an unbearably painful wound that he ultimately could not treat. Striving to find a cure, he continued to heal the sick and injured, while remaining eternally wounded himself. According to Kearney (1996) Chiron’s reputation as a great healer was related to his ability to express empathy and compassion for the wounds of others. In the ancient myths about healing, healers had the power to heal, precisely because they were vulnerable to trauma and pain (Goldberg, 1991). Jung (1951) was the first to consider the wounded healer as the therapist whose personal difficulties enhanced his or her capacity as a healer.

The myth of the injured healer reminds us of the importance of recognizing and accepting our own strengths and limitations and the value of connecting with others, with authenticity, sensitivity and respect. The wounded healer does not hesitate, when necessary, to communicate his own vulnerability and emotion, as this allows the patient to accept his human nature. This form of connection creates a healing environment that enables suffering to be alleviated or even transformed. Similarly, Wheeler (2007) argued that without the capacity to feel at a deep level -to be open to one’s own pain- therapists are limited in their capacity to relate to others and be therapeutic.

A basic concern underlying these interventions of psychologists was to create a more humane hospital for staff, patients and their families, a safe place of care that could promote agency and connection in a critical time in their life.

References

Anderson, H., & Swim, S. (1995), Supervision as collaborative conversation: Connecting the voices of supervisor and supervisee. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 14, 1–13.

Anderson, H. (1997) Conversation, Language and Possibilities: A Postmodern Approach to Therapy. New York: Basic Books.

Bakhtin, M. (1984) Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Minnesota, MN: University of Minneapolis Press.

Bertrando, P. (2007), The Dialogical Therapist: Dialogue in Systemic Practice. London: Karnac.

Burnham, J. (1993) Systemic supervision: the evolution of reflexivity in the context of the supervisory relationship. Human Systems, 4: 349–381.

Borrell- Carrio, F, Suchman, A., L & Epstein, R, M. (2004), The biopsychological model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann. Fam Med Nov-Dec;2(6):576-82. doi: 10.1370/afm.245.

Bowlby, J (1988), A secure base, Parent child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books.

Βrown, Β. (2012). Daring Greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent and lead. New York, NY: Penguin/Random House.

Campbell, T. (2003), The effectiveness of family interventions for physical disorders. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29, 263–281.

Cecchin, G, Lane, G, Ray, W. (2009).), Irreverence. A Strategy for Therapists’ Survival Thessaloniki: University Studio Press (in Greek).

Charalabaki, K, Thanopoulou, K. Kati, A. (2022), Family therapy training in the Greek public sector: the manualization of an experiential learning process through personal and professional development. In M. Mariotti, G. Saba & P. Stratton (Eds), Handbook of Systemic Approaches to Psychotherapy Manuals: Ιntegrating Research, Practice and Training. European Family Therapy Association Series.

Chronister, J., Fitzgeralnd, S. (2021). Psychosocial Aspects of Chronic Illness and Disability . In F. Chan, M. Bishop, J. Chronister, E-J Lee, Ch. Chiu (eds) Certified rehabilitation counsel or examination preparation. Νew York: Springer Publishing Company.

Davydow D.S, Zatzick D, Hough C.L., Katon, W., J. (2013). In-hospital acute stress symptoms are associated with impairment in cognition 1 year after intensive care unit admission. Ann Am Thorac Soc, 10(5): 450–457.doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201303-060OC.

Εlkaim, M. (2008), Αν μ’ αγαπάς μη μ’ αγαπάς. Αθήνα: Κέδρος.

Engel, GL.(1980), The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. _Am J Psychiatry ,_137, 535–44.

Frank (1995), The Wounded Story telle, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Hermans H.J.M. & Dimaggio, G. (Eds) (2004), The Dialogical self in psychotherapy, New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge.

Jung, C., G. (1951). Fundamental questions of psychotherapy, in H. Read.

M. Fordham, G. Adler &W. McGuire (Eds), The collected works of C.G Jung (Vol.16). Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press.

Kolb, D. A. (1984), Experiential Learning: The process of experiential learning.

Eaglewood Cliffs, N. J., Prentice-Hall, New Jersey.

Linnet, L. and Littlejohns S. (2007), Deconstucting Agnes- externalization in systemic supervision. Journal of Family Therapy, vol. 29, issue 3, 183-303.

McDaniel, S. H., Hepworth, J., and Doherty, W. J. (1992), Medical family therapy. New York: Guildford.

Neden, J. and Burnham, J. (2007) Using relational reflexivity as a resource in teaching family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 29: 359–363.

Nuzum D, Meaney S, O’ Donoghue K (2014), The impact of stillbirth on consultant obstetrician gynaecologists: A qualitative study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 121(8): 1020–1028.

Penn P. (2001), Chronic Illness: Trauma, Language, and Writing: Breaking the Silence. Family Process, 40/1, 33-52.

Rober, P. (1999), The therapist's inner conversation in family therapy practice: some ideas about the self of the therapist, therapeutic impasse, and the process of reflection. Family Process, 38 (2),209-28.

Rober, P. (2002), Constructive hypothesizing, dialogic understanding and the therapist's inner conversations: some ideas about knowing and not-knowing in the family therapy session. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28: 467–478.

Rober, P. (2005), The therapist's self in dialogical therapy: some ideas about not-knowing and the therapist's inner conversation. Family Process, 44: 461–475.

Rolland J.,S. Walsh, F. (2006), Facilitating family resilience with childhood illness and disability. Special issue on the family. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 18(5):527-38DOI:10.1097/01.mop.0000245354.83454.68.

Rolland, J. S. (2006), Genetics, family systems, and multicultural influences. Families, Systems, and Health, 24(4), 425–441.

Thanopoulou, Κ. (2024), Psychic Pathways of Grief. Stories of loss. Athens: Pedio (in Greek, in print).

Wade DM, Howell DC, Weinman JA et al. (2012), Investigating risk factors for psychological morbidity three months after intensive care: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care, 16(5): R192.

Wade DM, Howell, DC (2016), What Can Psychologists Do in Intensive Care? ICU. Management & Practice, Vol 16, issue 4, p 242-245.

Weihs, K., Fisher, L., & Baird, M. (2002), Families, health, and behavior. Families. Systems, & Health, 20, 7–47.

Wheeler, S. (2007), What shall we do with the wounded healer? The supervisor’s dilemma. Psychodynamic Practice, 13, 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753630701455838.

White M. (2007), Maps of Narrative Practice. New York: W.W.Norton.

White, M. and Epston, D. (1990), Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. New York: W.W. Norton.

Wigren, J. (1994), Narrative completion in the treatment of trauma. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice,Training,31,415-423. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.31.3.415.