Abstract. Systemic theory and practice were applied in the ICU of KAT Hospital, from 2019 up until the pandemic breakout, with the intervention, designed by the psychologists’ office in collaboration with the 2nd ICU. An innovative, for the Greek standards, multilevel support and empowerment of relatives was achieved, inspired by the basic principles of systemic and medical family therapy (MedFT). The purpose is to raise awareness and inform relatives in order to help them take care of themselves and cope with their patient's course. As initially hypothesized, relatives showed increased levels of stress, anxiety and depression symptomatology. Four interdisciplinary, psycho-educational cycles were conducted, comprising of five weekly meetings, for the patients' relatives. The intervention helped to improve collaboration between the surviving patients and their relatives and all health care professionals, as their hospital stay up to discharge would usually last for several months.

Key words: Systems theory, Medical Family Therapy, Intensive Care Unit, Psychologists' intervention

Introduction

KAT is a General Hospital in Athens and the largest orthopedic hospital and trauma center in Greece, operating 24 hours a day, every day of the week. It has a staff of about one thousand four hundred employees and can treat up to five hundred and fifty patients at a time, of which up to sixty-three may be critically ill and require ICU treatment. Our hospital has many medical specialties and the psychologist’s office cooperates with all the departments[1] of the hospital. The daily practice and experience of psychologist highlighted two important issues. Firstly, we observed the communication barriers of health professionals among themselves, and between themselves and the patients and their relatives. The second issue concerned the effects of hospitalization in the ICU, both on a physical and a psychological level, on patients as well as their relatives. These implications are described below based on the Post Intensive Care Syndrome(Sidiras, 2018). These two issues were the trigger for the design and implementation of the early intervention for the relatives of ICU patients, which aimed to empower the families as well as the hospital system itself. Our training and experience as psychologists in this hospital led us to an intervention based on the principles of systems theory and medical family therapy (MedFT).

Theoretical framework

Systems theoryAccording to the general systems theory, the concept of 'system' is defined as the set of elements that are in interaction and interdependence. Systems are defined by their structural characteristics, the relationship between their components as well as their function. For example, in human systems, the elements of the system pursue a common purpose. The key aspect of differentiation between systems is whether they are open or closed to the influence of the environment in which they belong (Von Bertalanffy, 1968). A system is most notably defined by the degree of interaction with other systems. Any change in any element of the system brings about changes in the whole system (Bateson, 1972). Open systems exchange matter, energy and information with the environment, adapting to it and influencing it. On the other hand, closed systems are theoretically isolated from environmental influences. In essence, when we talk about closed systems we refer to systems that are highly structured and of minimal feedback, since no system is completely independent of the super system. Another property of the system is homeostasis. The concept of homeostasis refers to the regulatory actions that take place when a deviation from the equilibrium state of the system is observed. In simpler terms, systems are attracted to equilibrium and stability (Sexton & Lebow, 2015).

According to this theory, the hospital, the ICU staff, the psychologist's office staff, the family, the human body, etc. could all be systems. As mentioned above, each system has an internal structure, function and an interactive relationship with the external environment. We could consider the body of an injured patient as a system consisting of several systems (circulatory, digestive, cardiovascular, nervous, etc.) that interact with a common purpose: survival. We could also consider the patient as being part of two super systems, his family and the hospital. A patient’s illness or injury has caused a disturbance of the homeostasis of his body, but also a disturbance of the homeostasis of his family. The ICU, as a part of the hospital, interacts with the patient's body aiming at his survival. The ICU also interacts with the patient's family and at this point the psychologist's office intervenes to broaden communication and increase interaction,and through regulatory actions aims to achieve the homeostasis of the systems.

Medical Family TherapyMedical Family Therapy (MedFT) is an evidence-based practice in which systems theory plays an essential role in understanding how systems in health care settings interact and influence each other (Davis et al., 2022). Medical Family Therapy is based on the biopsychosocial model, using systems theory and interdisciplinary collaboration (Hodgson et al, 2014). It represents a rapidly growing area of healthcare that combines the biological, psychological, social and spiritual levels of both patients and their families and healthcare professionals (Mendenhall et al, 2018). The basic idea is the collaborative treatment of patients and families facing health problems. This form of professional practice emerged from the experience of family therapists working in healthcare settings in the 1980s and 1990s. Those who practice medical family therapy need to be familiar with illness and its effects on patients and their families, understand the medical system and how to work with health care professionals, and be familiar with techniques that help families and patients manage the uncomfortable emotions that illness imposes on them. Additionally,it is necessary that oneis willing to bridge mental health and medical care, learn the medical culture so as to work constructively in a different context, involving different rhythms, spaces, and'language' (Davis et al, 2022).

Intensive care unit- ICUThe Intensive Care Unit is treating patients who have an acute, life-threatening, or medically complex condition or disease that requires close, continuous monitoring by specialized healthcare professionals. The ICU consists of many specialized healthcare professionals, who cooperate in order to keep the patient alive. It is a closed department/system where critical care physicians, intensivists, nurses, physiotherapists and other healthcare professionals work together as a team (Marshall et al, 2017). While research on family involvement in the ICU is still growing, it is clear that there are some key elements that are considered important in family care, and influence the patient's course, depending of course on the severity of their condition. For example, in a study where intensive communication through multidisciplinary family meetings regarding the care plan and outcome goals was implemented, it appeared to lead to a reduction in length of stay for ICU patients and a reduction in mortality (Lilly et al, 2003). Only a few ICUs have protocols that promote a family meeting as part of care or treatment planning (Cypress, 2017). Relatives require constant communication with the ICU health professional team,and additionally, would like to be involved in the patient’s care (Hetland, 2022). According to Jacob et al. (2016), the family needs information, communication, hope, support and closeness to their patient. The journey through the ICU begins when an acute, medically complex condition or illness that is life threatening, occurs for a person. The starting point is the admission to the ICU and the intermediate stations include new experiences such as the ICU setting, anxiety, stress, change in the patient's body image, and communication difficulties (Azoulay, 2005). Before the end of the journey, they will most likely encounter lack of preparation and gaps in communication. The last stations are either the discharge, or the end of the patient's life.

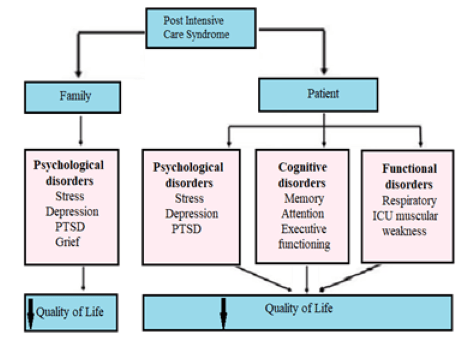

Post Intensive Care Syndrome - PICSThe family's journey does not end after the ICU patient’s discharge. The next station is Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS), which occurs in about 40% of ICU survivors and their families (Sidiras, 2018). Most patients survive until discharge from the hospital. This transition, although positive, often involves a new phase of recovery, with many challenges. ICU survivors, particularly those who required prolonged mechanical ventilation, experience more complications. Patients are at risk for symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and sleep disorders. Post-intensive care syndrome is defined as "a new or worsening decline in physical, cognitive or mental health status that occurs after critical illness and persists after discharge from the intensive care setting." In fact, the literature also describes the post-ICU family syndrome (PICS-F), where physical and psychological symptoms occur in patients' relatives, which are considered to be effects of the hospital stay that are still observed after discharge (Davidson et al., 2012, 2016). Family symptoms may persist for months or even years after discharge from the ICU, especially if the patient does not survive. In addition, research has shown that rates of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress are higher in family members than thepatients themselves (Fumis et al, 2015).

Figure 1: The post-ICU syndrome (Sidiras et al, 2018)

Figure 1: The post-ICU syndrome (Sidiras et al, 2018)

According to studies, among the risk factors for the occurrence of Family Syndrome after ICU, are poor healthcare professional-family communication, decision making, lower educational level, poor quality of life of surviving patients and having a loved one who died or was near death (Azoulay et al, 2005; Davidson et al, 2016).

To reduce the incidence of the syndrome, it is necessary to develop good communication strategies between healthcare professionals and family members of the ICU patient. There are specialized interventions that can be designed and implemented, starting from the patient’s admission to the ICU (Mitchell et al, 2016). One such multidisciplinary intervention is described as the ABCDEF bundle[2] according to Pun et al. (2019) and in addition to the health professionals' interventions with the patient, it involves family engagement and empowerment using communication strategies as well as engaging mental health professionals and other team members, and refers to the production of information leaflets for the families. In addition, the Diaries during the patient's stay in the ICU appear to reduce the occurrence of symptoms in the ICU survivor and their family (Kredenster et al, 2018).

Project presentation. The ICU intervention.

Taking into account the theory and research data, the intervention started with an assessment of the ICUs’ needs. First of all, an interdisciplinary communication between the psychologists, the director of the ICU and the ICU head nurse took place. A request emerged to support the diverse needs and concerns faced by ICU patients and their families. Once a week all psychologists were involved in the (daily) medical team meeting concerning the patients' progress, and every day one of the psychologists was present during the relatives’ ICU visit and the debriefing of the families by the doctors regarding the patients’ condition. The closed system of the ICU allowed us to be part of their daily life in order to understand how the ICU works, the condition of each patient, and to observe any communication problems between healthcare professionals and the family members. The intervention was designed to support families with patients who were hospitalized in the ICU. We hypothesized that participants would have high levels of anxiety, depression and stress. The assessment included a measurement of symptoms of family members[3] (N=78, 25 men and 53 women) which was performed utilizing DASS 21 (within 1 week of patient’s ICU admission). The measurements confirmed our initial hypothesis. More specifically, increased levels (severe and very severe symptoms) were present in 83.3% of the sample regarding stress symptoms, 72.9% regarding anxiety symptoms and 71.6% regarding depression symptoms (Panou, 2020).

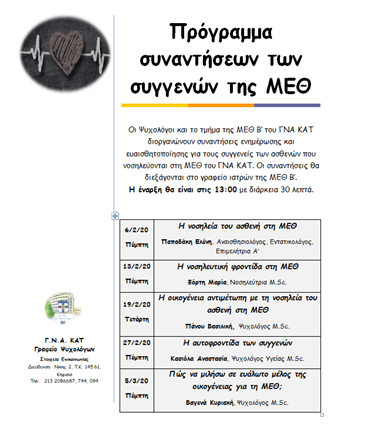

The interventionThe intervention began immediately after measurement, and five weekly multidisciplinary psycho-educational family support groups were conducted. An intensivist, a nurse and three psychologists carried out a presentation and discussion of a specific topic with relatives each week (Fig. 2). Meeting topics included information about the medical and nursing care that patients receive in the ICU, issues the family was facing due to the new conditions, self-care for relatives, and ways to communicate about the ICU with more vulnerable family members. The meetings were held before the midday visitation hours, in the ICU physicians' conference room. Information leaflets[4]were also designed, so that relatives could access information. The leaflets were distributed to relatives when their patient was admitted to the ICU (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Meeting schedule of the ICU relatives

Figure 2. Meeting schedule of the ICU relatives

Individual and family support was available when it was necessary. Sometimes family members need additional information and preparation before visiting theICU and their patient. ICU stay varies among patients and in this case, additional family support may be needed. As survival is not certain for all patients, preparation and bereavement management was also planned in the intervention design. In addition, counseling and family preparation was provided in cases of organ donation.

Figure 3. Information brochures for family support

Figure 3. Information brochures for family support

Another part of our intervention was the translation of a children's workbook for the ICU[1] . This offers information, adapted to the needs of children, regarding the ICU with photos, exercises and also a reference to emotions, in order to help children's participation in the ICU journey.

Discussion

Family therapists are well suited to work in healthcare settings because of their skills in psychological and relational assessment, diagnosis and treatment. They are valuable members of multidisciplinary healthcare teams, as they understand the ways systems are best configured and function, and have a wide range of skills to work with one or more individuals at a time.

Specifically in the ICU, which is considered a closed department/system with a specific structure and rules, shifting and expanding communication – be it between healthcare professionals themselves or between professionals and relatives - was a challenge. The transition from the conventional biomedical model to a new mode of Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Sensitivity (BPS-S) as supported by medical family therapy, in a department like the ICU was a challenging project. During the intervention, various forms of resistance, suspicion and communication barriers were observed, and it was there that the role of supervision played a very important role, as it strengthened our resilience to continue our project. Unfortunately, the pandemic forced us to stop the family support groups due to the strict measures. However, when needed, telephone support from the psychologist's office was available. Family support groups have not started yet, due to various difficulties, but families and patients are supported individually to this day.

The journey of patients and their families does not stop with the discharge from the ICU. As mentioned above, when the patients survived, hospital stay could last for several months. Families and patients are supported by the hospital psychologist's office up until discharge. In addition, the ‘Trauma, Illness, and Loss Psychological Support Office’ in KAT Hospital, is available for individual and family sessions for management and adjustment to life after hospitalization.

More and more studies point to the need to move from a biomedical to a biopsychosocial model of care. Healthcare needs to be governed by systems theory and MedFT, and providing information to healthcare professionals would be useful in order to gradually improve the care services provided, and reduce both hospital stay and the physical, mental, and psychological impacts experienced by healthcare recipients (Doherty et al, 2014; Anderson, 2016).

References

Anderson, B. R. (2016). Improving health care by embracing systems theory. The journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery, 152(2), 593-594. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.03.029.

Azoulay, E., Pochard, F., Kentish-Barnes, N., Chevret, S., Aboab, J., Adrie, C., Annane, D., Bleichner, G., Bollaert, P.E., Darmon, M., Fassier, T., Galliot, R., Garrouste-Orgeas, M., Goulenok, C., Goldgran-Toledano, D., Hayon, J., Jourdain, M., Kaidomar, M., Laplace, C., Larché, J., Liotier, J., Papazian, L., Poisson, C., Reignier, J., Saidi, F., Schlemmer, B. (2005). Risk of Post-traumatic Stress Symptoms in Family Members of Intensive Care Unit Patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 171(9), 987-994. doi:10.1164/rccm.200409-1295oc

Bateson, G. (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Cypress, B. S., & Frederickson, K. (2017). Family presence in the intensive care unit and emergency department: a meta synthesis. Journal of family theory & review, 9(2), 201-218. doi:10.1111/jftr.12193.

Davidson, J.E., Jones, C., Bienvenu, O.J. (2012). Family response to critical illness: post intensive care syndrome-family_. Criticalcare medicine. 40(2):618-24._ doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318218236ebf9.

Davidson J. E., Harvey M. A. (2016). Patient and family post-intensive care syndrome. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 27(2), 184-186. https://doi.org/10.4037/aacnacc2016132

Davis, C.E., Lamson, A.L. & Black, K.Z. (2022_)._ MedFTs' Role in the Recruitment and Retention of a Diverse Physician Population: a Conceptual Model. Contemporary family therapy. 44, 88-100. doi:10.1007/s10591-021-09627-0.

Doherty, W. J., McDaniel, S. H., Hepworth, J. (2014). Contributions of medical family therapy to the changing health care system_. Family process. 53(3):529-43._ doi:10.1111/famp.12092.

Fuke, R., Hifumi, T., Kondo, Y., Hatakeyama, J., Takei, T., Yamakawa, K., Inoue, S., Nishida, O. (2018). Early rehabilitation to prevent post intensive care syndrome in patients with critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 8(5). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019998

Fumis, R. R., Ranzani, O.T., Martins, P. S., Schettino, G. (2015). Emotional disorders in pairs of patients and their family members during and after ICU stay. Public library of science, One. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115332.

Hetland, B. D., McAndrew, N. S., Kupzyk, K. A., et al. (2022). Family Caregiver Preferences and Contributions Related to Patient Care in the ICU. Western journal of nursing research. 44(3):214-226. doi:10.1177/01939459211062954

Hodgson J., Lamson A., Mendenhall T., Crane D. (Eds) (2014). Medical family therapy: advanced applications. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-03482-9_8

Jacob, M., Horton, C., Rance-Ashley, S., Field, T., Patterson, R., Johnson, C., Saunders, H., Shelton, T., Miller, J., Frobos, C. (2016). Needs of Patients' Family Members in an Intensive Care Unit With Continuous Visitation. American Journal of Critical Care. 25(2):118-25. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2016258.

Kredenster et al, (2018).Preventing Posttraumatic Stress in ICU Survivors: A Single-Center Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of ICU Diaries and Psychoeducation_, Critical Care Medicine: 46 (12), 1914-1922._

Lilly, C. M., Sonna, L. A., Haley, K. J., & Massaro, A. F. (2003). Intensive communication: four-year follow-up from a clinical practice study. Criticalcare medicine, 31:394-399. doi:10.1097/01.ccm.0000065279.774

Marshall, J. C., Bosco, L., Adhikari, N. K., Connolly, B., Diaz, J. V., Dorman, T., Fowler, R. A., Meyfroidt, G., Nakagawa, S., Pelosi, P., Vincent, J. L., Vollman, K., Zimmerman, J. (2017).What is an intensive care unit? A report of the task force of the World Federation of Societies of Intensive and Critical Care Medicine. Journal of Critical Care, 37, 270-276. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.07.015. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.07.015.

Mendenhall, T., Lamson, A., Hodgson, J., & Baird, M. (Eds.). (2018). Clinical methods in medical family therapy. Focused issues in family therapy. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-68834-3

Mitchell M. L., Coyer F., Kean S., Stone R., Stone R., Murfield J., Dwan T. (2016). Patient, family-centred care interventions within the adult ICU setting: an integrative review. australian critical care, 29(4), 179-193. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.08.002.

Panou V., (2020)._Relatives of Critically Ill Patients of the Intensive Care Unit of KAT Hospital꞉ Investigation of Anxiety, Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Levels._MedicalUniversity of Athens.

Pun, B. T., Balas, M. C., Barnes-Daly, M. A., Thompson, J. L., Aldrich, J. M., Barr, J., Ely, E. W. (2018). Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF Bundle. Critical care medicine, 1. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000003482

Sexton, T.L., & Lebow, J. (2015). Handbook of family therapy: the science and practice of working with families and couples (1st ed.). Routledge.

Sidiras G. et al (2018), Post intensive care syndrome (PICS), Archives of Hellenic Medicine, 35(4):454-463

Von Bertalanffy, L. (1968) General System Theory: Foundations, Development, New York: George Braziller.

[1]For this we have secured permission from The ICU STEPS.

[1]https://www.kat-hosp.gr/ipiresies/iatriki-ypiresia/

[2] The ABCDEF bundle Assess, prevent, and manage pain; Both spontaneous awakening and breathing trials: Choice of Analgesia and Sedation; Delirium assess, prevent, and manage; Early Mobility and Exercise; Family engagement/empowerment

[3] Spouses, parents, siblings, children

[4] https://www.kat-hosp.gr/ipiresies/iatriki-ypiresia/tmimata/psixologoi/