As the years go by the judges that condemn you grow in number, Seferis ascertains, expressing his reflection and bitterness, and adds: “The pain is greater when you feel like a stranger in your own land”.

Half a century has passed and we are faced with the historical paradox, where it has come to the point where people who were not even there are invoking the Polytechnic uprising (“I was there too”) and are honouring it as a historical event - as it became the pride of our country and of Greeks all over the world, and one of the universal events of the youth movement – while more right wingers and fascists hate it and malign it.

It was there that all of us who were revolting, not just students, but also workers, farmers, and schoolchildren were chanting “six years are too many, they won’t become seven”, “it is now or never”, “fascism dies tonight”.

Beyond writing history, without even realising it during those three days, the uprising of November 17 1973 became the symbolic event that guides the continuation of fighting for young people, and it became a refuelling station where they could replenish their supplies and drop everything from the past that was weighing them down. The Polytechnic uprising in not owned by anybody, it belongs to the people who continue to fight, because he who fights does not have time to spare in disappointment.

The Polytechnic is a thorn in the soft underbelly of a society that is hypnotised. It is dangerous, it shows the way, there on Patision Avenue, it stands urging towards rebellion and daily awakening, and it inspires because it is not something that happened once in a distant past; it is a living memory, it resists the wear of time and every form of authority, it is held and carried by the upwards of 1103 wounded, and the upwards of 1500 arrested that night.

Those who died were not killed in vain. The names of more than thirty-four people who were killed are recorded, and then there are those that we will never learn of, because the dictatorship “buried” them, terrorising their parents and relatives. In the book “30 + 1 The Polytechnic lives”, their names are mentioned.

We honour our dead. It is the tradition of our civilisation since ancient times. Politics, citizen, the state, are not just words with a common root[1]. They are our civilization, the Democracy of saying good morning. They are not a mere part, an addition, they are the entirety of our existence and the abscess of our lives. And eros that is “unconquered in battle” does not last long. Because if it does, it will end up as a pleasant disgrace, that is why it does not leave the window open for love.

The polytechnic uprising is a revolutionary socio-cultural event, and its value will remain for the ages. The youths that march in the streets in demonstrations chant about it: “The Polytechnic did not end in ’73, bread, education, liberty”. The children long for the thing they never experienced. It is the hope for tomorrow, because they may never encounter it.

The Polytechnic is the past, the present and the future… It blew up in the faces of those who attempted to slander it, distort it, misrepresent it, take advantage of it, and even exploit it.

We were not heroes, and as Brecht said, “Unhappy the land that is in need of heroes”. They put us on a pedestal only to later try to tear us down with a resounding and deafening crash. They have not succeeded in 50 years. Quite the opposite, we now have squares and streets named after us.

When the children ask us, we cannot say that we were not afraid “facing the tanks, the army and, the rabid policemen”. We shared the fear and transcended it. We held each other’s arms and turned our songs and chants into fists, while the snipers were shooting and killing people in the surrounding streets, where our comrades had set up their barricades.

Collectivity, camaraderie and solidarity unified us, and became our greatest power. We did not make a turn on Patision Avenue to enter the Polytechnic School and occupy it. It was the pinnacle of our struggle, that began within our friendships, our romantic relationships, the anti-war movement in the U.S., Woodstock and The Strawberry Statement movies that were only played for one day in our country, or May of ’68. But most of all, it began with our belief in liberty and life, and our vision of changing the world.

We started organising ourselves in Student Activism Committees in our University Schools since 1969. The democratic people had started reacting at Seferis’ funeral, in 1971, that turned into a demonstration, with chanting and singing songs by Theodorakis during the funeral procession. Two years earlier, what was to follow became quite obvious during the mandatory school student event that was organised by the dictators, in honour of the Greek fighting prowess, on the 21st of April 1969. The booing and jeering by the students didn’t allow dictator Papadopoulos to give his speech.

When the dictatorship thought that it could enforce “order and security” through, court martialling, imprisoning, torturing and exiling, resistance fighters, and dissolving organisations that fought with declarations and dynamic actions from the very first moment… it was then that the youth disregarded all of this, the arrests and torture, and started organising local societies on a national scale, that helped recognise and coordinate against stooges that were placed in the governing boards of their schools.

The election that we were demanding since 1972, through student petition signings and court appeals, was our medium and our decisive way of fighting the dictatorship and the system that gives birth to dictatorships, as well as all those who supported the dictatorship, both local and foreign.

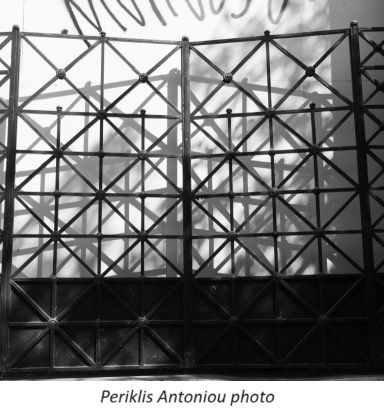

It was written on the two pillars of the gate of the Polytechnic, by the brush of Fine Arts student Giannis Kaylis from Distomo, whose murder in February of 1974 was presented as a suicide. There, in Exarcheia, on Dervenion street we fought to remove the terror and darkness from our schools, that had been enforced through the majority of our professors that were collaborators, the secret police, the informants and the ex-military government commissioners that had been appointed there.

We created a student movement, acted spontaneously for the most part, even when they forcefully drafted us into the army with the 1347 law in February 1973, following the trial of the 11 of the first Polytechnic events. Our colleagues occupied the Law School on February and March chanting “Bring our brothers back”. We had opened ourselves up to Greek society, disregarding the arrests, and terrorising the terrorists. The spontaneity of youth was self-organised in the Polytechnic occupation 8 months later. The self-regulation of the student movement during the Polytechnic occupation gave birth to the direct democracy of Solon, Cleisthenes and Pericles that we had been taught in school. Utopia had become reality and had found its place on the grounds of the Polytechnic.

We were a minority. Five thousand students of the total of 70,000 of all the schools in Athens. It was the same in Thessaloniki and Patras. It was not the entirety of the people, that is why we were shouting “Greek people support us” and “how can you be sleeping when they are killing your children” from the radio station. We became a great unity, and the assembly meetings at the schools became daily events.

We created the Coordinating Committee with revocable representatives. We spoke openly of freedom and democracy, in the country that gave birth to democracy, theatre and tragedy. The declaration by the Workers’ Assembly was an extension of our own and reached the construction sites and the workers. The assembly of the school students that had skipped their classes served as the dynamite of our hope. The Polytechnic became our stronghold, we felt free albeit besieged, like the fighters in Mesolongi in 1821; that is why our exit involved a tank.

With the radio station we broke our loneliness in the middle of Athens and made ourselves heard everywhere. The phrase “This is the Polytechnic” became our weapon, as we cried “soldiers, our brothers, we are unarmed, we are unarmed, our only weapon is faith in freedom and democracy. Don’t spill Greek blood”, and recited the national anthem as it had never been recited before. “This is the Polytechnic – this is the Polytechnic, you are listening to the radio station of the free students the free fighters of Greece”. Today it is like the alphabet for our children, like when we were taught how to read our first sentences back in our days at school.

Every year, they celebrate the Polytechnic uprising in schools. The Ministry of Education even declared it a holiday. Yet, it is not a simple anniversary; it is not a simple holiday. We did the first march on the anniversary. Seventy thousand of us marched to Caesariani to pay tribute to the 200 that were executed by the Nazis, chanting “EAM – ELAS – POLYTECHNIC”. The “NO” of resistance in our country is timeless. It comes from the battle of Marathon, through 1821, from there it goes to 1941 and 1973. It cannot fit in the embrace of a submissive “YES”…

In this country, apart from the financial, socio-political crisis, we also experienced the treachery against Cyprus, with the 1974 coup against Makarios, and the Turkish invasion. Leukios Zafeiriou, a fellow student, comrade and poet from Cyprus, participated in the Polytechnic uprising and experienced the treachery when he and other Cypriots tried to reach Cyprus and fight on a military ship, and were stopped by the commander of the Navy.

His mother, a poet and fighter from Larnaka, set herself on fire, at the age of 33, in honour of Grigoris Afxentiou, and Leukios wrote in March 1977:

“And as one by one

the white markings of spring

spring up on the hillsides

your sacred form

appears

bathed in joyful light

a bust with two teardrops

of a butterfly on the eyes

from the teargas

of time”

And… in June 1979 he writes the poem:

Negative for “Aris Velouchiotis” for the Polytechnic and Che, Che Guevara:

“Events are piled up

like food in the refrigerator

they dwindle in cooling

maybe they will endure the march

of time of the scythed chariots

they swirl around on the coroner’s table

the events of history

and with them the friends

who have started giving in

to the hint of “we are doing well” -

in seventy-three in the Polytechnic we were keeping

nix for liberty

now we lay on Persian carpets

and colourful armchairs

in paradise-like beaches we discuss

fighting tactics with a disabled

will

and disemboweled ideals

Che shakes his fists

stubbornly

the sweet image of Che

an archangel with flaming swords

on the time of interrogation

Che over the South American

slums

Che Guevara

years after the heavenly circumambulation

in Trikala square

of Aris’ head”.

And Evagoras Pallikarides, who was friends with Lefkios, writes on the tombstone of Demetrakis Demetriadis, the seven-year-old boy that was selling flowers and was killed by the English with a bullet to the forehead for daring to shout “Union, union, union”:

- And you slave boy, why do you stand and stare in sorrow?

- I do not have a gun captain

- Here, these rocks are good enough for you little one

And the young hero, the youngest of all grabs the stones to bring Liberty.

And I wrote “I hurt therefore I am” in “Ah Mourloskotomeno” and in my last book “We don’t have time to die”.

[1]T/N The words Politiki, politis, politeia, (πολιτική, πολίτης, πολιτεία) all derive from the Ancient Greek word polis (πόλις).