The following article addresses the connection between the arts and the systemic family therapy. In particular, a brief reference is made to the original idea of utilizing art therapy in family meetings, and the benefits of using the arts in family therapy are presented. In the course, methods, techniques and exercises are described that combine various systemic model theories (experiential, strategic, Bowen theory, multi-generational, structural, solution-oriented and narrative) with art (visual, music, movement).

Keywords: art, family therapy, systemic therapy, visual arts, music, movement, art therapy, family art therapy

Introduction

Loss-Death: Difficult concepts, emotionally overwhelming. How can we give meaning to the experience of loss and death? Can the words be combined to pass on the message? Kia Thanopoulou 2nd year trainer at the Family Therapy Unit of the Psychiatric Hospital of Attica, during the lesson "Processes of loss within the family" chooses painting as the vehicle to travel through the specific training unity. With the help of colours, trainees depict on paper, how they perceive death and loss.

Quite often we find no words, and other times words become the drops making the river flow viciously, and drift us, as well. The hand catches the paintbrush or the colour pencil, draws a line slowly slowly and then another, and another one without knowing, in advance where it leads us. An image emerges. Other times, the image is already there, from the beginning. What remains is to be depicted on paper. However, has it be depicted the exact way we had visualized it?

Time for reflection: "what does this image tell us?", "what does the group observes?"... Through art, we externalize our deepest thoughts and feelings, thus facilitating our personal development.

Art Therapies

Man being creative, expresses and communicates, relaxes and is liberated through art. Art and especially the combination of various forms of art (dance, song, visual art, storytelling) are used to connect people with themselves, with others (group) and with their natural environment (Rogers N., 1993). "Ceremonies in which an indigenous healer or shaman might sing, dance, make images, or tell stories recall the early roots of psychology and psychiatry" (Malchiodi, 2003, p. 106).

In ancient Greece, we have many examples of the use of arts for therapeutic purposes: Epidaurus Health Center, Asclepius Health Centers (Ευδοκίμου- Παπαγεωργίου, 1999). "The psychic opportunities provided by art and its processes offer a rich field for therapeutic utilization. This field is the basis on which art therapies are built» (Γιώτης, Μαρβελής, Πανταγούτσου, Γιαννούλη, 2019, p. xv).

Art therapies are therapeutic approaches that use corresponding forms of creative expression. The most well-known are: art therapy (which utilizes the medium of visual arts), drama therapy, music therapy, dance or movement therapy and play therapy. Also, therapy through photography, literature, video, poetry and expressive art therapy, which utilizes and combines various expressive means, such as art, music, movement etc.

In our times, art therapies meet with all standards that modern psychotherapeutic approaches call for, based on the biopsychosocial model of understanding health, disease and treatment. Art therapies follow the principles and terms established by the therapeutic frameworks and the training and research protocols applied in the scientific field (Γιώτης et al., 2019).

The first steps of Family Art Therapy

Kwiatkowska (1978, p. xi) states that "art therapy is older than family therapy but has developed more slowly". She had been involved in the field of art therapy since its inception, under the guidance of Naumburg, who is considered a pioneer of art therapy (Wynne & Wynee, 1978). "The idea of using art therapy with the families came through accidental participation of family members in individual art therapy sessions with patients" (Kwiatkowska, 2001, p.29).

Early in her career as an art therapist, in 1958, at the Department of Adult Psychiatry of the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, Kwiatkowska began to focus more and more on the role of the family in mental health. Many times, during the visits of the family members, the patients wanted to show them, the work they had created in the context of their individual art therapy. This work did not often receive the appropriate response, as relatives were shocked and expressed negative comments. In an effort patients are not discouraged and family members continue to be interested in the patient's artistic creation, Kwiatkowska suggested that the family takes an active part in the art session. "The art production and interaction of this fraction of the family were so revealing and produced such unexpectedly interesting material that we wondered what would happen if we included the whole family regularly in the art program" (Kwiatkowska, 2001, p.29).

Kwiatkowska's early family work offered so much in the field of research and family art therapy, that a large number of authors relied on it: Landgarten, Linesch, Riley & Malchiodi, Sobol (Malchiodi, 2003). Others have contributed to promoting visual arts in family therapy, in counseling and psychology: Selekman, Freeman, Epston, Combs and Gladding.

Benefits of using Art in Family Therapy

The multiple benefits of therapy through the arts, in the emotional, cognitive and physical functionality of individuals and groups have been reported and analyzed by many authors (Rogers, 1993; Kwiatkowska, 2001: Malchiodi, 2003; Ευδοκίμου- Παπαγεωργίου, 1999; Tσέργας, 2014 etc.). These advantages are also evident in family therapy through art/family art therapy; however, there are many additional advantages to using the arts in family therapy:

Family art therapy allows all generations to have an equal "voice" through art expression. Guttman (op. cit. Manicom & Boronska, 2003) points out that children may find it difficult to talk about how they feel and what they think about their family when asked directly. By creating images, their views can be examined more openly and recognized. Especially in working with children, family therapists have used a variety of nonverbal approaches, such as games, puppets, toys and drawings to make space for the children to tell their stories (e.g. Freeman, Epston & Lobovits, 1997; Berg & Steiner, 2003 op.cit. Rober, 2009). Adults who have difficulty communicating verbally can also benefit from using art in family therapy.

"Family art therapy enhances communication among family members and uncovers, through the process as well as the content of the art task, family patterns of interaction and behavior" (Riley & Malchiodi, 2003, p.363). How the family manages, the actions of one of its members, during the healing process, often reveals the way in which similar situations are treated at home (Landgarten, 1999). The creation of a common project by all members of the family, gives us valuable information about the functioning of the family system, through conditions that are less formal and less influenced by defense mechanisms, than those in the purely verbal psychotherapeutic process (Kwiatkovska, 2001). Family art evaluation is related to the above. It is "an effective method of diagnosing family dynamics, where the conclusions are useful for planning family therapy or other treatment model" (Δάλλη, Φλέβα και Βράνα-Δάλλη, 2019, p.482).

The use of art in systemic therapy offers a new way of communication. For the client in individual therapy, visual expression (through painting, sculpting, music, movement, writing and video) can be an important vehicle for communicating difficult family issues to the therapist. A simple drawing or collage can be the means by which the client "brings the family in", and it offers an opportunity to discuss roles within the family and issues in the client’s family of origin (Riley, 1985).

Through the aforementioned way of communicating, family members have the opportunity to use their creative potential in problem-solving, broadening their perspectives and improving their relationships (Riley & Malchiodi, 2003). Learning to be creative increases our ability to innovate and approach any situation from a new perspective (Jackson, 2014). Creative arts can be used as a means of self-care and reflection (Jackson, 2014). "The art experience facilitates interactions, an attitude of openness, insight, and the adoption of new skills. It also furnishes the family with a stage for rehearsing new roles and communication styles, since art therapy participants can afford to take a chance on dealing with each other in a new way through the non threatening art experience. Families soon learn that their symbolic art therapy efforts serve as trials for taking grander risks at home" (Landgarten, 1987, p. 7).

Shirley Riley (2003) states that there are many reasons why art therapy is preferred as a method of working with couples. As mentioned, depicting problems provides a new perspective and introduces a new way of communicating. Expression through art can highlight marital issues from another perspective and provide an opportunity for both the couple and the therapist to establish goals and produce a treatment plan. Each partner desires that the other person sees the world "through his own eyes". This is difficult to achieve only on a verbal level. The use of images facilitates the above process (Landgarten, 1999). The existence of short moments of cooperation or care could be the basis for further increase in such moments. The value of the art language is that allows the individual to talk about painful issues through the security of a lump of clay or a piece of music. By focusing on the work of art and activity, the couple avoids entering into the process of mutual accusations (Landgarten, 1999).

Systemic psychotherapy and art - Systemic theory in visual psychotherapy

"Perhaps the real biggest hit of the family therapy movement was its power to fold back upon itself and change" (Ηοffman, 2001, p.11).

Art therapy with families emerged during the past several decades as the natural consequence of the development of family therapy theories. The integration of systemic theory has been a central concern to practitioners using art expression with families (Riley & Malchiodi, 1994). Many systemic models have been used as a framework for family art therapy, including the experiential, the strategic, the structural, the solution-focused, and the narrative approaches. (Riley & Malichiodi, 2003)

Experiential family therapy (V. Satir)

According to Landgarten (1999), the experiential family therapist through art, participates in the treatment actively and feeds the family with innovative visual experiences that focus on emotions, spontaneity, authenticity, awareness and understanding. Virginia Satir, a pioneer in the field of family therapy, used art and games/play to involve young children in therapy (Armstrong & Simpson, 2002).

One of the basic intervention techniques she developed is family sculpture. The aim was to depict the emotional relationships of the family through the attitudes and positions of individuals (or objects) in the space. "The symbolic presentation of family relationships in this way takes place without the help of digital language and for this reason is usually very quickly understood" (von Schlippe & Schweitzer, 2008, p. 187). Although this technique was originally introduced by David Kanto, Fred and Bunny Duhl, it was used extensively by Satir. The example of Satir was followed and elaborated by Peggy Papp, Olga Siverstein, Elizabeth Carter, Maurizio Andolfi and others (Dalos and Draper, 2010)

Peggy Pap, David Kantor and Fred Duhl presented, in the 80's, the method of "couples choreography", which is an extension of the technique of Satir family sculpture (Ζαφείρης, Ζαφείρη, Μουζακίτης, 1999). Based on the above technique, Peggy Papp, Michele Scheinkman and Jean Malpas developed a protocol for the use of sculpture in family therapy (Papp, Scheinkman and Malpas, 2013). "Both the family sculpture and the couples choreography help in the diagnostic evaluation of the family in terms of the two-way relationship between physical space and emotional distance of its members, and allow the therapist to determine the type of changes the family needs" (Ζαφείρηςet al, 1999, p.130).

Strategic Family Therapy (J. Haley)

The strategic viewpoint with the systemic stance may use "the artwork as a vehicle for prescriptive and paradoxical intervention, giving attention to the resolution of problems" (Langarten, 1987, p.5). According to Jay Haley (Zαφείρης et al, 1999), any type of communication behavior can belong to either the symmetric or the complementary type. The symmetrical relationship of individuals, where each member in the relationship is active and energetic, can be reflected in the improvisation of a musical duet. "When only two people are playing, it becomes fairly obvious where the musical interaction breaks down. After discussion of the attempt, the therapist (or family members) can make suggestions to help improve the communication, and the members playing the duet can then experiment with new ways of playing together and experience improvement in the session" (Miller, 1994, p. 47). In the process, they could correlate with and improve their verbal communication.

In cases people have difficulty listening to each other, "music echo" could be an exercise suggested by the therapist. One person will play a short sequence and another will repeat it (musical echoing). According to Miller (1994, p.47), "this type of echoing can help restore communication, because it encourages family members to listen and respond to each other in a validating and non-threatening manner. This experience is essential for work in families where the children’s feelings are not validated or perhaps not acknowledged. Likewise, this type of echoing exchange helps to interrupt patterns of blaming, accusing, and shaming that are automatic, unconscious responses. Through the process of echoing musically, family members can develop skills of listening and responding. Both the parents and children can experience the validation of being heard".

Another technique of strategic therapy is home assignments. For example, the therapist asks family members to keep a visual diary (with painting or collage) where they will express feelings and thoughts from their daily life or in relation to a specific event. The purpose of this assignment is to make it easier for people who have difficulty expressing feelings.

Bowen's approach to family therapy

One of the basic concepts of Bowen’s theory (1996) is triangulation. Triangulation between the members of the family may emerge during the art work. In this case, two people, being in tension with each other, involve a third person pointing their dissatisfaction to him in order to reduce their tension. In the case of triangulation, the therapist leads the patient to activities which emphasize differentiated and autonomous functionality (Landgarten, 1999). "The Bowenians with a direct style emphasizing triangulation, can point out this aspect as it is revealed in the unit’s artwork; they will engage the clients in tasks that stress differentiated autonomous functioning" (Landgarten, 1987, p.4). A musical improvisation can contribute to such a process of "self-differentiation". Each member can play his/her own improvisation and at the same time, interact musically with the family unit as a whole. By repeating this process, each member can be trained to express him/her-selves in his/her own way, and at the same time listen and respond to the ways others express themselves. Once this is achieved, the sense of interaction is achieved and can be reproduced in verbal communication (Miller, 1994).

Riley & Malchiodi (2003) suggest another process of "self-differentiation", via a visual way. The patient is invited to draw his family. Then, the therapist encourages the client to cut himself/herself with scissors and guess how the other members of the family will relate to each other once the client is out of the picture. At the same time, the patient could process his own feelings as a cut-out member of the family. What could he/she do being free from the family frame? "This simple metaphorical intervention can assist a client in addressing the neglected developmental task of individuation" ( Riley & Malchiodi, 2003, p. 367).

Related to the above is Bowen’s concept of "undifferentiated ego mass". "This concept refers to blurred boundaries and entanglement. This can be exemplified through ‘lumped together’ artwork, where it is difficult or impossible to identify the contribution of each member due to overlapping, mergins and connecting forms" (Landgarten, 1987, p. 6).

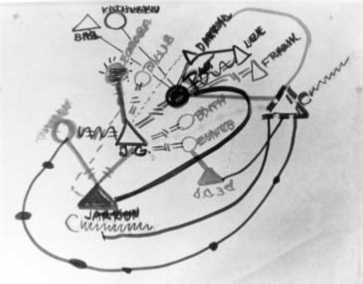

Based on Bowen's theory, McGoldrick and Gerson formulated the genealogy method. The genealogy summarizes complex information about family systems using specific symbols (Goldrick & Gerson, 1999). These symbols can be enriched with colors or supplemented with photos of people or their favorite objects or even some special family events.

Shirley Riley (2003) refers to the term "art therapy genogram". The therapist explains the meaning of the family map and "suggests that the relationships and generational patterns can be individually portrayed and augmented by using color and images to expand the content of the symbols" (Riley, 2003, p. 392). In this technique, no attempt is made to follow the traditional pattern as suggested by McGoldrick and Gerson. For example, family members who took a protective role could be green and those who were violent could be black. The use of colors that reflect behaviors gives the genogram life and helps the individual or family members to identify inherited characteristics and behaviors.

"Art therapy genogram" from the book Handbook of Art Therapy (Malchiodi, 2003, p.392)

Multigenerational treatment approach (I. Boszormenyi-Nagy, H. Stierlin)

"The multigenerational approach introduced systemic therapy to the perspective of exploring, beyond the current situation, how meaning emerges from behaviors, experiences or even symptoms taking into account the legacies of previous generations and questioning whether they have been realized or were feasible" (von Schlippe and Schweitzer, 2008). An example of "multigenerational family therapy" is presented in the book "Family Art Therapy" by Landgarten (1999) and concerns a patient in the final stage. The sessions were attended by the whole family (three generations) to whom the opportunity was given to deal with the loss, to express feelings and thoughts, and each generation to be confronted with psychological material, which is mainly related to the respective developmental stage is going through (Landgarten, 1999).

The multi-generational model is a technique that could be combined with the Family sculpture. Von Schlippe and Schweitzer (2008, p. 189) report on the above technique that we can playfully familiarize the family with a systemic view: the circularity of behaviors in social systems, the multi-generational perspective and much more.

The term "parentification"(" parental child" or "adult child"), according to Stierlin (von Schlippe and Schweitzer, 2008), refers to the participation of children in parental duties, sometimes in marital duties. The attribute of the parental role to the child by the parent(s), and the adoption of this role by the child can be projected during the creation of the art work. According to Landgarten (1987, p.6), "Parentification exists when there is inappropriate reversal of the parent-child roles while creating their product".

Structural Family Therapy (S. Minuchin)

Boundaries and structures are particularly important in Structural Family Therapy (von Schlippe & Schweitzer, 2008). "Structuralists, who are active directors, may calculate art project interventions that purposely interrupt the family’s usual transactional behavior and require members to rearrange their roles. They may also designate directives that manipulate a trial realignment of subsystems and change boundaries" (Langarten, 1987, p.5). For family units that need structure and boundaries, tray and boxes are employed since limitations are defined by the raised sides and tent to prevent acting during the art work (Landgarten, 1999).

In addition to the visual arts, the structural family therapist can use other art forms such as music, both in the evaluation phase and in the therapeutic intervention phase. Music has unique qualities that make it effective in group or family gatherings. A primary quality of instrumental music is that it is a means of communication, consisting of the elements of language (sounds and rhythms), without, however, bringing forward the specific correlations of the words. "Hot" topics that could automatically provoke the usual intense emotions and behaviors can be temporarily placed in the background. "The choice of musical intervention is especially congruent with structural family therapy, which concentrates on patterns of interaction in the present" (Miller, 1994. p39).

An example of the use of music in families with dysfunctional parent-child boundaries is the following: The therapist may ask the parents to direct their children in musical activity -from the choice of instruments to how and when to play. If both parents are present, they can be instructed to take several minutes for a private "parents’ meeting" to plan how they wish to conduct the activity. The parents can assign specific instruments to the children or give them a limited choice of instruments. They may also give specific musical parts or open the activity to an improvisation. This allows the parents to act as a unit, an experience often missing in the dysfunctional family. The parents could direct the children when to start or stop playing, increase and lower volume, by using their voices and/or hand signals. Following the musical piece, the parents may have another brief "parents’ meeting" and return to say what they liked and did not like about the piece, and what they would like for a second part (Miller, 1994).

Music offers a neutral context in which the relationships of family members are evaluated through the element of rhythm. Rhythm is a formidable quality because it demands structure. By observing how the family responds to the demands of rhythm, the therapist can construct a formulation as to how each member responds to structure in general (Miller, 1994). For example, within the context of a strong musical rhythm, some family members may join "on the beat", others may come in on the "offbeat", still others may take liberties and improvise "sub rhythms" within a given meter, and still others may resist the musical activity altogether. Whatever formulations the therapist derives about the family interactional styles by observing their rhythms they provide a useful starting point for understanding the family. In the process, these formulations, are subject to revision as more information is accumulated (Miller, 1994, p.40).

Postmodern family therapies

According to Peter Rober (2009, p.118) there is a long tradition of taking seriously the nonverbal mode of communication in family therapy (eg Watzlawick, Beavin & Jackson). In the family therapy room, non verbal modes of communication have been helpful in enriching the therapeutic process (eg. Andersen, Gil, Rober), Peter Rober (2009), who was inspired by the work of Michael White, Tom Andersen, John Shotter and other family therapists, developed a protocol for the use of painting in couple therapy. In his approach, the dialogue between the clients and the therapist is more central than the content of the drawing, and as he states, this approach fits with the dialogical approaches to family therapy.

In solution-focused art therapy, the therapeutic relationship starts with mutual goal setting and a cooperative attitude, with the target of neutralizing resistance. In the initial session, the client may be asked to set some goals through a collage or a simple drawing. Expression through art in the early phase of treatment allows the client to speak out this problem in a tangible form, and to inform the therapist about the presenting issues through images. When the therapist explores the art product with respect and listens to how the client perceives it and its meaning, the client feels heard. In a family session, every member might be asked to draw his or her own view of the major difficulty or the "most pressing problem", he/she thinks in the family system. The images open the way for subsequent discussion and demystification of the presenting problems (Riley & Malchiodi, 2003).

"The following brief case may help to illustrate this point. When asked to draw the most pressing problem, a parent may depict her child with undesirable friends who she feels have led her son or daughter astray. The child might draw the "terrible" teacher that has singled him out for unjust punishment. The therapist has the opportunity to take this one step further by asking parent and child to fold or cutaway the persons outside the family represented in their drawings and place their images of parent and child close together so that they touch. They are then asked to draw a solution together on a single sheet of paper to combat these external forces. For the parent and child to draw on the same page is an introduction to the notion that they must work together to problem solve. Proceeding sessions could focus on dual drawings that invite multiple ways to cooperate (e.g., mother depicts visiting school and child could illustrate bringing a few friends over to the home)" (Riley & Malchiodi, 2003 p.84).

Similar elements to solution-focused therapy are found in narrative therapy (White & Epston). The basic principles of narrative therapy complement those of art therapy, which makes it a particularly useful approach in work with children, adults, and families. Narrative therapy mainly uses verbal means - storytelling and therapeutic letters - to help people express their problems. In the narrative approach of art therapy (or in narrative art therapy), the expression through art becomes a way of externalization with additional benefits in the therapeutic process. For example, presenting the problem through a work of art (drawing, painting, collage, photo, video, etc.) is a natural way of separating the person from the problem. Through art, the problem becomes visible helping the person to get the proper distances from it.

Freeman, Epston and Lobovits (1997) approach expressive activities as an essential part of the narrative therapy approach, especially with children and their families. They state that "an external conversation is easily enhanced by other forms of expression that children prefer, such as play and expressive art therapy" (Freeman et al, 1997, p.11).

Conclusion

The above literature review fully supports the multiple ways of connecting art with systemic family therapy. Art therapists who have developed the systemic view, utilize the process of art work and its content, in both the phases of "evaluation" and "therapeutic intervention" (Landgarten, 1999; Riley, 2003; Miller, 1994). Similarly, systemic therapists through creative expression can enrich their therapeutic work even if they do not know some art from in depth (writing: Penn, 2001; "family sculpture": Papp, 2013; drawing: Rober, 2008, 2017).

The systemic approach and art therapy have much in common that makes for them easier to combine. "Drama therapy and the systemic psychotherapeutic approach are the two reference frameworks that are combined within the psychotherapeutic work and interact at the levels of the purpose of psychotherapy, the goal of therapeutic interventions and the choice of therapeutic methods. The focus of both approaches on health and not on pathology is a common basis for their combination in therapeutic practice" (Ζαφειροπούλoυ, Κασταμονίτου & Παπαθέου, 2019, p.111).

Similarly to drama therapy, other art therapies are combined with the systemic psychotherapeutic approach, expanding the role of psychotherapy and at the same time the therapist's framework. Finally, we must emphasize that the use of various art forms (art, music, movement, video, photography, poetry, etc.) in family therapy is a relatively unexplored area of treatment, it deserves further research, and can be practiced to a greater extent.

References

Armstrong S. & Simpson C., Expressive Arts in Family Therapy: Including young children in the process. Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 30 (2) σ.2-9, 2002.

Bowen M. (1996), Τρίγωνα στην Oικογένεια. (μετάφραση Γκίκα Ε., Λεβή Μπ., επιμέλεια- εισαγωγή: Χαραλαμπάκη Κ.). Αθήνα: Ελληνικά Γράμματα.

Γιώτης Λ., Μαραβέλης Δ., Πανταγούτσου Α., Γιαννούλη Ε. (2019), Πρόλογος Επιμελητών στο Η συμβολή των Ψυχοθεραπειών μέσω Τέχνης στην Ψυχιατρική Θεραπευτική. Επιμελητές: Γιώτης Λ., Μαραβελής Δ., Πανταγούτσου Α., Γιαννούλη Ε., Συντονιστής: Παπαδημητρίου Γ.Ν. Αθήνα, Εκδόσεις Βήτα, σελ. xv-xix.

Dallos R. & Draper R., (2010), An Introduction to Family Therapy. Systemic Theory and Practice. 3rdEdition. New York: Mc Grew Hill.

Δάλλη Α., Φλέβα Α., Βράνα- Δάλλη Π. (2019) Οικογενειακή Εικαστική Αξιολόγηση, στο Η συμβολή των Ψυχοθεραπειών μέσω Τέχνης στην Ψυχιατρική Θεραπευτική. Επιμελητές Γιώτης Λ., Μαραβελής Δ., Πανταγούτσου Α., Γιαννούλη Ε., Συντονιστής: Παπαδημητρίου Γ.Ν. Αθήνα: Εκδόσεις