Frisina, M. (2025). Genograms and Clinical Practice in Addiction Treatment: From Words to Images, and Back [JD]. Systemic Thinking & Psychotherapy, 27, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.82070/syst20252707

Introduction

Clinical practice in addiction treatment is a fascinating yet demanding field that confronts us with patients trapped in a cycle of repetitions they cannot escape. This loss of freedom manifests on multiple levels: language becomes impoverished, and narratives turn into closed and inevitable stories; the range of relational positions shrinks; the relationship with time focuses solely on the immediate effects of the substance*. (*I chose the word substance to translate “le produit”, because it includes drugs, alcohol, etc.)

The genogram—or rather, the various genograms—provides us with a framework and a clinical tool to address these difficulties: it broadens the perspective on addiction from the individual user to their relational context and situates the person within their story, allowing them to reclaim it. A classic and rigorous tool, yet also multifaceted and adaptable to different clinical practices, the genogram creates an intermediate space to conceptualize change, co-construct new interpretations, and mobilize resources. In this chapter, we propose a version called the "relationship map", which uses photography as a tool to help analyze the role of the substance in the addicted person's relational context.

An empty word

We perceive reality and give meaning to our experiences through language (White, 2007). Telling stories allows us to relate to others, share, understand, and order the events.

Our narratives are fluid, diverse, and constantly adapting to our trajectories and experiences. However, difficulties can alter how we make sense of reality through language. Similarly, our stories can imprison us in relational dynamics we cannot escape.

For over 15 years, my clinical work in addiction treatment has consistently confronted me with these aspects. “Without alcohol, I can't live”. “Cocaine is everything to me”. “Gambling is the only thing that makes me feel alive”. “Drugs have always been my only refuge”. Addicted patients’ narratives are closed, disconnected, and marked by inevitability, necessity, and impossibility. These are absolute, almost timeless stories, leaving little room for contemplating change. The rigid and relentless repetition of substance use is accompanied by disenchanted, empty language. Among addicted individuals, the loss of freedom is reflected—or perhaps begins—with the impoverishment of language (Frisina, 2020). The diversity of narratives is reduced to a single story, where the substance is the sole protagonist.

From Family Rituals to Addiction Rituals

The addicted person structures their days around obtaining the substance, using it, hiding the abuse, and avoiding withdrawal, which is unbearable even in anticipation. Over time, the repetition of these actions becomes highly codified, eventually forming genuine addiction rituals (Frisina, 2021).

The rituals of substance use gradually replace family rituals, separating the addicted person from the rest of the family. Waking up at the same time, sharing meals, going out together—these shared habits, the silent daily architecture of belonging, are sacrificed on the altar of substance use. The family environment then intervenes and adopts controlling behavior to prevent or reduce drug consumption: checking a partner’s breath for alcohol, confiscating their credit card to stop cocaine purchases, taking away car keys to prevent them from driving. Calling at regular times to assess, by voice, whether promises of abstinence are being kept. The family also develops substance-related rituals, even if only as a futile attempt to prevent its use (Anastassiou, 2003; Frisina, 2020). The range of relational positions is reduced to the simple alternation of substance use and ineffective prevention attempts, transgression and control, in an interactive dance that traps everyone involved. The loss of freedom, which defines the addicted person’s relationship with the substance, extends to the entire system.

Like a mirror between language and behavior, narratives are impoverished, and relational positions are reduced.

Repetitions and Immediacy: The Suspended Time of Addiction

Beyond language and relational patterns, addiction profoundly alters the relationship with time. Addiction operates immediately: the substance acts instantly and always in the same way. This is one reason why the addicted person replaces relationships to others with relationships to the substance, which is always the same and predictable: "Alcohol never disappoints me". "Cocaine will always be there for me, waiting". "When I gamble, in that infinite moment, nothing else exists". The future is not anticipated, except in the concern of obtaining the substance, and its horizon is that of daily -always identical - addiction rituals. The past is inaccessible through language: narratives repeatedly return to the present of the substance, its unbearable absence, its necessity. The rituals of substance use trace an unchanging pattern of gestures, day after day. The days follow one another identically, marked by the substance’s cycle: obtaining it, using it in secret, managing withdrawal. Within these repetitions, time passes without leaving a mark. This constant return to the present makes it difficult to access the patient’s past story, just as the future cannot be envisioned beyond a few days ahead.

The "Relationship Map": A Genogram to Navigate Clinical Work in Addiction Treatment

The loss of freedom and the feeling of helplessness experienced by the addicted person can, by isomorphism, be mirrored in the therapeutic process. Repetitive addiction rituals create patterns that are difficult to decipher, eluding the therapist’s hypotheses. The patient’s empty and disenchanted language rarely strays from the substance, offering little material for co-constructing alternative narratives. The reduced time horizon, flattened onto the present, leaves no access to history or trajectory of the past. The therapist, like the system, finds little room for imagining change.

In this context, genograms constitute a privileged tool to liberate, support, and enrich language. They provide both an interpretative key and a tool for broadening intervention possibilities. We use the plural "genograms" to emphasize their diversity, their richness in variations, and their adaptability to different contexts. Since its development (Bowen, 1978), the genogram has been a "living" tool that has evolved alongside systemic therapy (Daure, 2010; Daure & Borcsa, 2020; McGoldrick et al., 1990 & 2020). While sharing common roots, different forms of the genogram demonstrate the vitality of systemic thinking in constant motion: the imaginary genogram (Ollié-Dressayre & Mérigot, 2017), the landscape genogram (Pluymaekers & Nève-Hanquet, 2008), the emotional genogram (Citterio & Iori, 2020), the individual systemic therapy genogram (Daure, 2017). A rigorous yet flexible tool, the genogram adapts to the specificities of different clinical contexts. Here, we propose a version called the "relationship map", designed for use in clinical practice in addiction treatment.

Instructions: A Framework, not a Protocol

The instructions for the relationship map consist of three steps, each followed by a discussion with the patient. The first two steps are normally addressed in a session, while the third takes place between one session and the next, in order to offer more time for reflection and to create “a connection” between the different sessions.

1. “Today, we invite you to use a tool to represent the relationships, current or past, that can tell us something about the difficulties you struggle with. These relationships that, in one way or another, you believe are linked to the reason why you chose to come here. We ask you to take this large sheet of paper and place your names and the names of these individuals. You can decide where to position them, what size to use, and how to graphically represent the connections with you, and between them”.

2. “Now, we ask you to add the substance and illustrate your relationship to it, and where you place it in relation to the others”.

3. “We then invite you to select a photograph that represents your relationship to the substance and the role it plays in your life. Then, you can also choose other photographs and images to tell a story about the other relationships depicted on the map”.

The Ideas Behind – or within – the Relationship Map: externalization of the symptom, relational functions of addiction, expansion of the time horizon

The first step marks a distinction from the traditional use of genogram. The system represented is not necessarily the family system but rather the system "shaped" by the problem. Who reacts – and how – to substance use? Which relationships are most affected by these behaviors? These aspects emerge through a description whose boundaries do not necessarily coincide with family ties. This is not an alternative version of the genogram but a complementary one, shedding light on different aspects of the relational system.

The second step, which involves including the substance in the genogram, is based on the principle of externalization (White, 2007). According to narrative therapy, individuals come to therapy with the belief that their problems reflect deep truths about themselves. In other words, with the idea of being the problem, and of being defined by the problem: “I am a cocaine addict”. It becomes difficult to describe oneself beyond the symptom, as it becomes the only lens through which one understands oneself.

Externalization is the process that helps create a distinction between identity and problem description. This difference creates space that allows a new subjective positioning and a margin to imagine change. Including the substance in the relationship map helps separate it from the patient’s identity while also illustrating the nature of their relationship with it.

Furthermore, including the relationship to the substance facilitates reflection on the role that substance uses plays in the relational chessboard. Addiction is then situated in a broader context than just the person who uses the substance, which enriches the process of hypothesizing on the relational function of the substance. Indeed, patients often recognize the individual function of substance use: "I drink to forget", "cocaine gives me confidence", "when I gamble, I feel alive, I feel like I exist". However, it is more difficult to think about the role that the substance plays in relation to other relationships. Genograms provide a view of the subject in context, illustrating how addiction becomes the organizing principle of the system. Although dysfunctional, substance use is the "third element" that regulates the addict's relationships.

Conversations with the patient, resulting from the genogram, help us co-construct keys to interpreting all these patterns. Alcohol use then becomes, for one patient, their only way to escape family expectations. In another case, medication misuse seems the only way to bring back – even if it is through concern - a partner who is drifting apart. For a young adult, cocaine became the mechanism preventing him from leaving a family that perceives differentiation as a threat to belonging. Placed within its relational context – thanks to the genogram, – the symptom regains its meaning and liberates language whose place the symptom had taken.

In the instructions, patients are invited to describe significant past and present relationships. This offers an interpretation of both horizontal (present) and vertical (generational) interactional dynamics (Daure, 2010; Daure & Borcsa, 2020). This aspect is especially crucial in addiction, where the time horizon is reduced to the immediacy of substance use. Thinking beyond the crisis, and into a broader temporal framework, expands possibilities for change. Genograms reveal intra- and intergenerational dynamics. In many cases, addiction, even if "silent" (not officially recognized), has already been present in previous generations. The replacement of family rituals with addiction rituals facilitates the transmission of the symptom. This phenomenon reinforces the closed and inevitable nature of addiction narratives, making it feel like a “family destiny”. In such cases, it is essential to use the genogram to highlight differences. If a substance appears across generations, did it serve the same role? The same functions? What else was transmitted? Intergenerational patterns should not be interpreted as a linear cause-and-effect chain. Through language and therapeutic space, transmission can be released from the control of the symptom and become a participatory process once again. This dynamic allows individuals to be repositioned and reclaim their personal stories.

The utility of genograms in relation to time is not limited to the past, but also is expanded on possible openings towards the future. As Salaün (2020) notes, genograms can have an anticipatory character and can facilitate reflection on future possibilities and change. In this sense, relationships are seen as evolving processes rather than fixed states. For instance, a patient might be asked, “If you could, how would you change your place in the relationship map?”

From Words to Images, and Back

Now, let’s focus on the third step of the instructions and its specificity: using photographs. For therapists, language is a privileged tool for joining with patients. However, there are always aspects of experience that are not “dressed” in words, that remain "unspoken". Asking patients to describe a relationship through the choice of a photograph aims to help enrich language that in addiction is often disenchanted, emptied, and impoverished. The image – and the reflection of the choice – facilitates access to metaphorical language. Metaphors, as "meaning condensers", allow for more articulated representations of one's position and relationship to the substance. One patient, for example, chose a photo of two people, in a friendly context, in which one was pulling the other towards them. Commenting on the image, he confided to me: "Alcohol is like an overbearing friend". The image revealed two crucial aspects, later explained through words during the session: the role of the substance to compensate for loneliness ("friend") and the boundary-setting difficulties in the relationship ("overbearing"). These dynamics later resurfaced in discussions in other contexts (in his childhood, the patient felt like "the antidote to my mother's loneliness because my father was rarely around”, and he had already felt the difficulty in setting limits to parental expectations).

Another patient selected a portrait of a beautiful woman in dim lighting and said, "Cocaine is my mistress". This metaphor opened discussions about belonging, betrayal, boundaries, and difficulties in his romantic relationship, elements that led him to seek refuge in his "mistress".

Asking patients to use an image to describe relationships (with the substance and with others) shifts the focus from individual traits to interactional patterns. Indeed, we believe it is important that the unit of analysis be the relationship, not the individual as an isolated entity. As Strogatz (2003, p. 231) notes, "It’s the pattern that matters, the architecture of the relationship, not the individual entities themselves".

Photographs allow us to capture something beyond words – but without taking its place, on the contrary to support and expand its capacity to connect with. From words to images, and back.

A Clinical Case: Stefano and Diane

Stefano drinks in secret. With precise and silent gestures, he organizes his days to create gaps, away from Diane’s gaze, where he can surrender to alcohol. Diane observes him. She scrutinizes his way of walking and checks the intonations of his responses. She searches for traces of use in the small details of his behavior – until her fears become certainties. Often, this choreography of their exchanges is silent, requiring no words. Sometimes, however, it takes the form of an explosion. Stefano clenches his fists and screams about how unbearable it is to feel controlled in the relationship. Diane yells and throws kitchen objects to the floor, watching them shatter with the same fragility as Stefano’s promises.

Stefano says, “I drink because Diane controls me, I feel infantilized”. Diane responds, “I control him because he drinks in secret”. In this repetitive dance that imprisons them, each one sees only the other’s side, blind to their own contribution to the pattern. Their days, marked by an alternation of heavy silences and sudden arguments, repeat identically, as if suspended in time. The geometry of their gestures repeats itself, forming a worn-out ritual that takes the place of words.

During the first sessions, their narratives continuously return to the alcohol, as if drawn by gravitational force. It is difficult for Stefano and Diane to talk about themselves beyond this perpetual crisis. Questions about their past are quickly abandoned, like a path they are reluctant to follow. In an apparent paradox, alcohol is at the center of every sentence, and yet the words remain empty, failing to convey the real stakes of addiction.

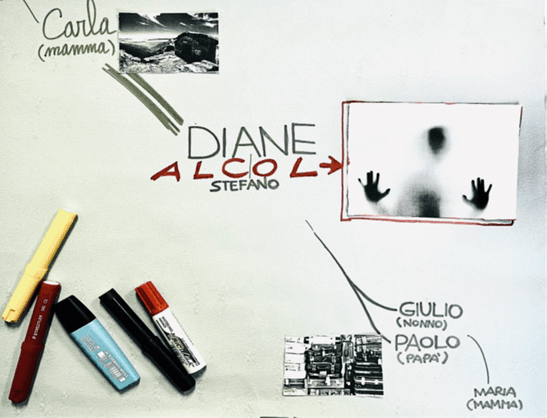

We then decide to introduce the relationship map. Stefano and Diane listen in silence to the instructions. For the first time, their eyes meet. They move the paper closer together, and then Stefano, hesitantly, begins to write their names in the center. Diane’s name is at the top, much larger. His name, just below, smaller, as if crushed by it. Then, a little farther away, almost at the edge of the page, he writes the names of his father and grandfather. A black line suggests a connection between them and him, though it doesn’t quite reach his own name. _“My father and grandfather also drank. They were workers. Before returning home, they would shake off the dust and exhaustion by drinking at the bar across from the factory. My mother would wait in silence, hiding her concern in the unnecessary gestures of tidying an already spotless kitchen. I never heard them argue, yet my mother suffered. My father and grandfather both died young, around 55 years old. I think it was due to the consequences of alcohol, though my mother never openly said so”. Diane listens quietly, then begins to draw. She writes only her mother’s name, linking it to hers with two bold, repeated lines. “My mother raised me alone. My father left us when I was very little. He built a new life in Germany. I never had contact with him again”.

In this initial version of the relationship map, there are few people and connections. If addiction-based systems are characterized by withdrawal into themselves, isolating them from others, it is important to remember that the notion of absence often precedes the emergence of the symptom (Anastassiou 2003, Frisina 2020). An absence that has already been shaped over generations, long before it is embodied in the unbearable void, real or anticipated, left by alcohol. And yet, despite its sparseness, the relationship map is highly suggestive. A genogram does not need to be complete to tell a story. Often, it is precisely in its omissions, its voids, and its silences that we can discern trajectories and repetitions. Moreover, as discussions with patients progress, the genogram can be expanded (Daure and Borcsa 2020). Step by step, through words, through conversation. Resources are added to the system “shaped” by the symptom.

Stefano speaks of his father and grandfather only in relation to alcohol. In family systems, when addiction rituals replace family rituals, often the only thing that gets passed down is the substance, as if through an inevitable mechanism. Yet within these repetitions, one can glimpse an attempt at repair. Stefano does not simply keep drinking without questioning it. Today, he is in therapy. He struggles within a system that he himself tightens around him. He seeks to understand. Diane, too, reacts differently than Stefano’s mother. At times, she observes quietly. But she also reacts, she screams with rage, she tries unsuccessfully to prevent his drinking. Unlike Stefano’s family of origin, they both allow themselves time for a crisis. For a demand. I ask Diane why she chose to represent only her mother. She replies, “Sometimes I wonder if I will end up like her. Alone. Because with every drink, Stefano drifts further away from me. But I hold on to him, I try not to let him go. He is absent and present at the same time”. Diane, too, is confronting the same issue that passed down to her: the absence and the fear of abandonment.

Stefano speaks of his father and grandfather only in relation to alcohol. In family systems, when addiction rituals replace family rituals, often the only thing that gets passed down is the substance, as if through an inevitable mechanism. Yet within these repetitions, one can glimpse an attempt at repair. Stefano does not simply keep drinking without questioning it. Today, he is in therapy. He struggles within a system that he himself tightens around him. He seeks to understand. Diane, too, reacts differently than Stefano’s mother. At times, she observes quietly. But she also reacts, she screams with rage, she tries unsuccessfully to prevent his drinking. Unlike Stefano’s family of origin, they both allow themselves time for a crisis. For a demand. I ask Diane why she chose to represent only her mother. She replies, “Sometimes I wonder if I will end up like her. Alone. Because with every drink, Stefano drifts further away from me. But I hold on to him, I try not to let him go. He is absent and present at the same time”. Diane, too, is confronting the same issue that passed down to her: the absence and the fear of abandonment.

I then ask Stefano and Diane to include alcohol in their relationship map. Their thoughts seem to align. They both point to the same spot on the paper and write “alcohol” in red in the narrow space between their two names. “It is always between us, right here in the middle”, Stefano says.

I look at the paper and ask them whether the word “alcohol” separates or, rather, connects their two names. “Both”, Diane replies. “It connects us because we are always engaged in the same struggle. But it separates us because when Stefano drinks, he stops talking to me. He becomes like a ghost. I try to shake him, then I give up. I step back”. The map begins to reveal a possible relational function of the substance, it acts as a mechanism that regulates closeness and distance in their relationship. A bond, and a barrier.

When we move to the third step of the instructions, Stefano and Diane choose the image of an opaque screen to represent their relationship with alcohol. A photograph in which, the silhouette of a person can barely be discerned behind a glass pane. Just a faint outline, nothing more. “We thought back to the previous session. To the idea that alcohol both connects us and separates us. That’s why we chose this image”, Stefano says. Diane adds, “We each face our struggles on our own side of the screen. So close, and yet irreversibly distant. Unreachable”. We continue discussing the image. The opacity of the screen. “It is probably opaque because it keeps us from looking ahead. From understanding what direction to take. Since Stefano started drinking, I feel like I am reliving the same day over and over again”. Diane’s words hint at another possible relational function of alcohol: it keeps the couple suspended in time, protecting them from whatever awaits them beyond. I ask what would happen if alcohol were no longer there to screen their future. If they could finally reach the other side. “If I stopped drinking, we would probably have a child. We’ve talked about it. But in the current situation, it’s not possible”. “I would love to have a child with Stefano. But I’m afraid I’d end up raising it alone, like my mother did”. “And I don’t want to be an absent father. Like mine. Like my grandfather”.

Desire, but also fear of repeating the same trajectory as previous generations. The genogram situates addiction within a broader relational context, beyond the individual who drinks, in a temporality more complex than the suspended time of repetition. I ask them what they would need to overstep the screen. They both answer: “Trust”. That same trust they have long since lost, bit by bit, with each broken promise, every betrayed intention. They no longer believe in each other’s words. And yet, they are still here. Together.

Conclusion

In Japanese, there are two words for "trust": 信用 (shinyou) and 信頼 (shinrai). Shinyou, it’s to trust in the sense of believing what someone says. This trust is oriented toward the past, in the sense of believing that what one says corresponds to what happened. Shinrai, however, it’s to trust in one's relationship with someone. This trust is oriented toward the future, in the sense of being able to rely on the other. Often, the two types of trust coincide, but this is not always the case. It is possible to have shinyou without shinrai, for example: believing that what someone tells us at a given moment is true, without necessarily trusting them as a person. For Stefano and Diane, the opposite is true. They no longer have shinyou in the sense that their words have lost meaning. But they still have shinrai—they still believe in their relationship. Session after session, they work to regain trust in their words and their ability to break free from the patterns that have been shaped by previous generations.

Gradually, their relationship map grows richer—with images, with metaphors, with tools that help guide their interaction with words. The time horizon expands, to include what came before them, but also what will follow. The meaning of the past trajectory, and the choice of the future trajectory.

Addiction draws a repetitive functioning, suspended beyond time, in which days unfold identically, dictated by substance use. Like a mirror, narratives become rigid and empty, and language and words lose their power to weave connections. Faced with these difficulties, the genogram provides therapists and patients with a space to co-construct new interpretations. It restores a contextual understanding of symptoms, reveals relational dynamics, and allows individuals to reconnect with their stories and reclaim ownership of them. Transmission ceases to be a predetermined fate and becomes a framework for imagining new possibilities. The relationship map, by incorporating photography and visual metaphors, enriches language that would otherwise be depleted. Images open a gap between the patient and the substance: within this space, through visual experience, the individual can reclaim their role as the protagonist of their own story (Jacques, 2020).

References

Anastassiou, V. (2003). Les distorsions des fonctions parentales dans le système alcoolique. Alcoologie et Addictologie, 25(3), 191–199.

Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. New York, NY: Jason Aronson.

Citterio, N., & Iori, V. (2020). Fa.g.e Family genogram of emotions. Un nuovo strumento per lavorare con le emozioni in terapia. Milano: Mimesis Edizioni.

Daure, I. (2010). Le génogramme avec les familles. Le Journal des Psychologues, 281(8), 27–30.

Daure, I. (2017). La thérapie systémique individuelle. Une clinique actuelle. Paris: ESF Éditeur.

Daure, I., & Borcsa, M. (2020). Les génogrammes d’aujourd’hui. La clinique systémique en mouvement. Toulouse: ESF Sciences Humaines.

Frisina, M. (2020). Sul bordo del caos. Complessità, terapia narrativa e dipendenze. Milano: Mimesis Edizioni.

Frisina, M. (2021). Perturbando l’opacità di un sistema dipendente. Quaderni SIRTS, 2, 43–44.

Jacques, A. (2020). Traversée de l’enfer et réhumanisation. L’outil photographique comme médium de résilience chez des survivants Burundais. Quaderni SIRTS, 1(2020), 37–47.

McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Petry, S. (2020). Genograms: Assessment and intervention. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

McGoldrick, M., & Gerson, R. (1990). Génogrammes et entretien familial. Paris: ESF Éditeur.

Ollié-Dressayre, J., & Mérigot, D. (2017). Le génogramme imaginaire. Entre liens du sang et liens du coeur. Paris: ESF Éditeur.

Pluymaekers, J., & Nève-Hanquet, C. (2008). La formation des thérapeutes familiaux et le génogramme paysager: un outil de développement personnel et de supervision. Cahiers critiques de thérapie familiale et de pratiques de réseaux, 41(2), 97–106.

Salaün, F. (2020). Handicap et métamorphoses familiales. In I. Daure & M. Borcsa (Eds.), Les génogrammes d’aujourd’hui. La clinique systémique en mouvement (pp. 63–74). Toulouse: ESF Sciences Humaines.

Strogatz, S. (2003). Sync: The emerging science of spontaneous order. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.